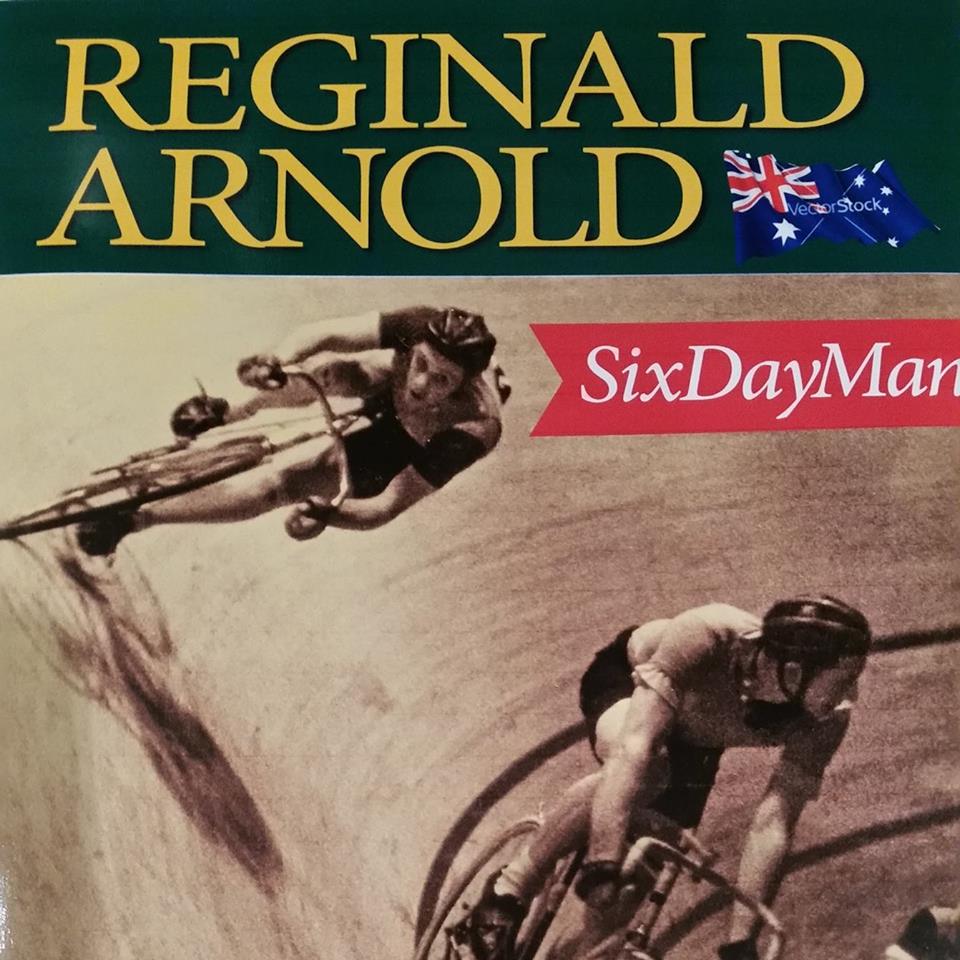

Early most mornings an elderly gentleman could be seen walking his dogs around the township of Banora Point in northern NSW, stopping to chat with passers by, joggers and other walkers. Few would have realised that this friendly and humble stranger was once the champion of the world … Reginald Arnold. Mr Arnold passed away on July 23 2017 aged 92.

“He had ridden 103 sixes for 16 victories, was twice European champion and held track records at Vel d’Hiv Paris, Brussells, Munich and Zurich.”

On Australia Day 2012, Banora Point’s Reginald Arnold received an Order of Australia medal for services to Australian sport. Surprisingly, the nomination came not from within the sport of cycling itself, but from his neighbour across the road, who had been fortunate to a sneak a peek inside the champion cyclist’s photo album which is rarely opened these days.

Reg Arnold was once one of the most famous and highly paid cyclists in the world. He made his name as a six-day man, but as well as being one of the best six-day riders in the world Reg was also a world class sprinter, an omnium rider and was a very good pursuiter, making the round of eight in several World championships.

He also rated number three in the world behind the derny. As a roadman he was an excellent handicap rider, a great time-triallist, he could climb and descend mountains, and in a road race bunch sprint was almost unbeatable. Reg Arnold, or Roger as he was called in Europe, was the complete all-round cyclist.

Given His First Bike

Reg Arnold’s career began in 1941 when he was given a bike by his brothers Lindsay and Fred and joined Ashfield cycling club in Sydney. Because Reg was blind in one eye from a childhood accident, his mother was not keen on the idea. However the 16-year-old quickly began to make a name for himself as a track sprinter and was soon the holder of several state titles. In 1943 several Sydney clubs, including Ashfield, who were dissatisfied with the Australian Cycling Union decided to form a breakaway association. Many of the best riders joined the rebel group (called the Australian Cycling Association), including the Arnold brothers. At this time a similar breakaway group had formed in England and in 1946 the English ‘British league of Racing Cyclists’ issued an invitation for two riders to attend the Brighton to Glasgow stage race. Alf Strom, the ACA Road champion and Reg Arnold the ACA track champion, were chosen to attend.

The Brighton to Glasgow was a disappointment. A 52-day boat trip meant Reg was badly out of form and was forced to withdraw after a couple of stages. Attempts to earn a living racing in England proved fruitless and the penniless Australians were desperate. By chance they met a Belgian stranger who took them to Gent and introduced them to Oscar Daemers, the famous manager, promoter and trainer. Seeing their potential, Daemers took the Australians into his outfit and coached them in the intricacies of professional track cycling, in particular the madison or ‘teams race’ as it was called back home. After months of hard training in the Belgian winter of 1946, they were ready to race.

Unfortunately the Australian breakaway cycling association was not affiliated with the International Union and the ACU took the opportunity to refuse Arnold and Strom clearances to race in Europe. After months of negotiations Daemers finally convinced the Australian officials to relent – but the massive fines imposed had to be paid by wealthy contacts as nobody in Australia had the money to release the debt. But with this obstacle overcome, the Australian pair began to gradually experience some success in the two and three-hour madison events. Daemers decided to try to get them contracts for the six-day races, which was where the good money was, in Gent, Antwerp, Paris, Brussels and Berlin. But 1947 and early 1948 proved to be disappointing, as the gruelling six-day format proved too difficult to master.

Six-day racing was by no means easy. Many of the famous riders refused to do it, and no amount of money could tempt them. Many a roadman had attempted six-day racing only to fail the test in humiliating fashion. Reputation counted for little in the battle against the guile of the six-day men, whose experience and ability to endure pain could silence the boasts of the biggest names in cycling. Inhumane distances coupled with severe sleep deprivation meant that fatigue, crashes and physical breakdowns were certain. A six-day race in the ‘40s and ‘50s was typically between 2,400 km and 3,000 km in length. Berlin was the longest at 3,600 km. The maths is simple: to do 3600 km in six days is 600km daily per team. Assuming the team splits the time on the bike equally, that’s 300km per day each, with only three hours sleep allowed.

During the winter track season of 1948-49 Arnold and Strom managed some creditable results, notably a third place in the Gent six-day and a third in the European madison championships. The following season began with an invitation to the New York ‘Six’, in the city which began six-day racing in 1899. In a thrilling battle, which was only decided in the final minutes, Arnold and Strom took their first six-day victory and the world sat up and took notice.

The Australians were now a real force to be reckoned with. The next 12 months saw three more victories in the Berlin six-day races of March and December 1950, and Antwerp in February 1951. After four more podium finishes in six-day events, the rankings for season 1951-52 were published and Reg Arnold was declared the number one six-day rider in Europe. The Australians then confirmed this by winning the European madison championship in January 1952, the unofficial world title. In the following weeks Strom-Arnold won the Antwerp and London six-day before a crash in Munich disrupted Reg’s season. After battling his injuries for some months, Reg decided to come home to Australia for a break. He was missing his family, the warm weather, and his mother was not well.

Welcomed Home By Fans

Reg Arnold’s arrival in Australia in April 1953 was greeted with excitement by the rank and file fans who had followed his success via the newspapers. Cycling officialdom was less enthusiastic and it was soon clear that even after seven years, the old jealousies had not healed. All attempts to gain an invitation to any track carnival in the country were futile, and he could not gain a start in the big road race tours as no team wanted him. He had a ride in the State Titles at Nowra in August, then won the Sydney 95 mile Grand Prix at Centennial Park the following weekend before entering for the seven-day Tour of the West, held over rough roads in country NSW. Despite riding solo against eight other teams including Speedwell and Malvern Star, Reg finished second to Hec Sutherland. Four days later he was on the start line for the 200km Goulburn to Sydney Classic.

Reg’s older brother Fred had won this race the previous year, and so the result was never in doubt. The headline in the following day’s newspaper read “Arnold’s easy win” as he rode away from all contenders to add his name to the honour roll. Again, riding solo, Reg then managed a third placing in the Herald-Sun Tour of Victoria in October, but still no job, no team, and no track races eventuated. The traditional Christmas Track Carnivals came and went, and Reg was not invited. In fact for the entire 1953-54 Australian track season, Arnold was ignored. Between November 1953 and April 1954 the champion was a spectator at the Australian velodromes.

But the Director of the Melbourne board track at Essendon, Ted Waterford, was having second thoughts. Reg Arnold would certainly draw crowds of fans to his carnivals. Waterford was Australia’s premier promoter. His carnivals boasted an incredible line up of Australian and International stars, names like Reg Harris, Enzo Sacchi and Russell Mockridge. Waterford invited Reg to race an international madison race at the Essendon Board Track. Reg partnered with his brother Lindsay to dispose of the other teams which included such names as Sid Patterson, Hec Sutherland and Graeme French. In a repeat race the following month, the Arnolds repeated the win.

Melbourne based businessman Bruce Small had also noticed Reg, and approached him with an offer to join the Malvern Star Team. Bruce had Hec Sutherland, Eddie Smith and Peter Anthony and offered Reg a monthly salary along with bikes, clothing and equipment. Reg jumped at the opportunity. After training solidly in June and July 1954, the Malvern Star team began by whitewashing their first race, the Tour of Tasmania. They dominated every stage, every sprint, every KOM and the final GC read Arnold first, Smith second and Sutherland third. The international track champion’s ability to climb and descend mountains astounded the spectators and other competitors.

They also finished 1-2-3 in The Advertiser Tour of South Australia, Smith and Arnold went 1-2 in the Sydney to Melbourne Tour, Reg won the Echuca Tour and they were first, third and fourth in the Herald-Sun Tour (won by Sutherland). In short, they won every major road race and tour that year. The one Reg really wanted to win however, was the Melbourne to Warrnambool. It was here however he had a problem with the handicapper. In the 277km Melbourne to Wangaratta (won by Smith), Smith and Sutherland were given the scratch mark while Arnold was given five minutes. When the team arrived at the Cobram 100km handicap they discovered that Reg was again placed on second scratch, so the three protested the decision by withdrawing from the race.

There followed a newspaper article in The Argus where the state handicapper defended his decision with the ridiculous statement, “Arnold has no reputation for being a road rider in Victoria”. But the real payback was meted out on the start line at Melbourne to Warrnambool, where Smith and Sutherland were placed on scratch with John Beasley. A further seven riders were given four minutes, and Arnold was off 10 minutes. As it turned out, the scratchmen travelled just 20 metres before crashing on tram tracks and were forced to withdraw from the race. Nearing the finish of the 260km epic, and with the four minute bunch almost upon them, Reg launched a daring solo attack which lasted 16km before he was caught. Fearing he would be beaten in the sprint by Billy Guyatt, Reg again attacked with two kilometres to go, he held a gap of 150 yards but was caught just metres from the line to finish eighth. He later declared that losing the 1954 Warrnambool was the biggest disappointment of his career.

Despite a fantastic road season and Bruce Small’s offer to set Reg up in a big bike shop in Melbourne so he could continue to ride for Malvern Star, Reg decided to head back to Europe in early 1955. His old partner Alf Strom had other engagements so Reg teamed up with Russell Mockridge and the two competed in dozens of madisons and omniums with a lot of success. Russ did not like sixes so Reg and Sid Patterson teamed for Zurich, Gent and Antwerp in the lead up to the Paris six-day race of 1955. In an attempt to hinder the collusion and illegal deal making between the top teams of the period, the promoter of the Paris six insisted on national teams, and required teams of three riders rather than the usual two. As Strom was unavailable, Reg and Patterson convinced Mockridge to be their third man. The story of what happened at Paris’s Vel d’Hiv track is one of folklore and legend, but somewhere among all the double-crossing and scheming, the Australians were tactically brilliant and snatched the victory while the others argued among themselves.

Antwerp decided to try the three man format and Reg was asked to team with Jean Roth, the brilliant Swiss sprinter, and Tour de France star Stan Ockers, the reigning world road champion. Antwerp had added derny racing to the program, a bonus considering Reg was a great derny rider and Ockers had just set the world hour record behind the derny on this, his home track. Despite fierce opposition from the Dutch team of Gerrit Schulte, Arnold-Ockers-Roth won the race to the delight of Ockers’ home crowd.

By this time, Strom had retired so Reg approached the Italian Ferdinando Terruzzi, and found in the 1938 Olympic tandem champion his ideal partner. Together they rode 23 sixes, winning Gent 1956, Antwerp and Dortmund in 1957 before being forcibly split up by the race promoters. The results were becoming so predictable that the spectators would not pay to come and watch. With Terruzzi, Reg Arnold won his second European madison championship in Copenhagen in 1957. Reg’s second European championship cemented his reputation as one of the world’s greatest teams race riders. He was a cycling promoter’s dream. The big money offered to the six-day stars was dependent on reputation, performance, and showmanship. Reg had all three. He boasted nine six-day victories, two European championships, and was a crowd favourite for his courage, showmanship and personality.

Reg Arnold rode with and against all the great road and track cyclists of that time. He partnered Rik Van Steenbergen to win his fifth Antwerp sash in 1958 and then followed it up by winning Gent later that year with Rik van Looy. The two Riks held five world road titles between them. With the world motor-paced champion Walter Bucher, he won Zurich in 1959. After some more sixes with Sid Patterson in 1960 (also a dual world champion) Reg was reunited with his old buddy Terruzzi, with whom he won Essen and Milan in 1961. Other notable champions he partnered in six day races include Jean Stablinski, Rudi Altig, Peter Post, Fred DeBruyne, Paul DePaepe and John Tressider. Some famous opponents included Bobet, Anquetil, Coppi, Koblet, Timoner and Kubler.

His last race was the Antwerp six of Feb 1963, teamed with the nine time European derny champion Peter Post and Tour de France star Willy Vannitsen. The dream of retiring on a victorious note was spoiled by the team of Rik van Steenbergen-Palle Lykke-Leo Proost, who were on the same lap but held a points advantage. Aged 38 and a half, Reg Arnold announced his retirement from professional cycling after the race.

Despite offers to stay in Europe and become a trainer or manager, Reg was keen to return home to Australia. He had been 17 years living in Belgium and he missed his family and friends. When he arrived by boat in mid 1963, there was no ticker tape parade, no media interest for Australia’s great ambassador, and Reg slipped quietly back into the anonymity of Australian life. His old mate Bruce Small was working on the Gold Coast and Reg joined him there, selling land for him on one of his developments, the Isle of Capri at Surfers Paradise.

In Australia few people cared who Reg was or what he had done. He had ridden 103 sixes for 16 victories, was twice European champion and held track records at Vel d’Hiv Paris, Brussells, Munich and Zurich. He did not expect recognition in Australia, seek it or want it. A superstar in Europe, he was anonymous to the general public at home. He is still remembered by many of the old-time cyclists who read of his exploits in newspapers and old cycling magazines. But apart from the Murwillimbah Cycle Club who stumbled upon him and made him their patron, he has not received the recognition afforded to other greats of the period like Mockridge, Patterson, Lionel Cox or Dunc Gray. He no longer owns a bike, his interests these days being golf, with his grandsons playing professionally. A number of hip replacements have meant that he does not play golf himself anymore, or walk as much as he used to.

Early most mornings an elderly gentleman can be seen walking his dogs around the township of Banora Point in northern NSW, stopping to chat with passers by, joggers and other walkers. Few would realise that this friendly and humble stranger was once the champion of the world.

All photos courtesy of the Arnold family.