Just on 35 years ago the Tour descended into utter farce. Herbie Sykes revisits the mother of all doping scandals…

Just on 35 years ago the Tour descended into utter farce. Herbie Sykes revisits the mother of all doping scandals…

On the eve of the 1978 Tour de France, the 75th anniversary edition, the cycling world was being re-ordered. The Merckx generation had retired, and so all of France looked towards a charismatic new star, one Bernard Hinault.

Stroppy and belligerent, this Hinault was the Breton archetype. Incapable of taking a step back off the bike, he was both a warrior and a winner on it, a tour de force. He’d started turning heads immediately he joined the professional ranks, but had become a French household name the previous June. At the Dauphiné he’d blasted into the yellow jersey, and looked nailed on to keep it. Descending the Col de Porte, though, he misjudged a bend before a live TV audience. Now, in one of those sickening, gut wrenching cycling moments, he simply disappeared down a ravine. As millions of his countrymen looked on utterly mortified, the cameraman dared to peer, in real time, over the precipice. Miraculously a small tree just beneath the road had broken Hinault’s fall, and saved his life. They hoisted him back onto the road, blooded but somehow not broken. Astonishing…

Adrenaline coursing through him, he remounted and continued his furious descent, still first on the road. On the final ascent into Grenoble, however, he climbed off his bike in tears, the full horror of what might have been seemingly upon him. Cyrille Guimard, the sagacious DS of his Renault team, somehow managed to persuade him to go again. We’ll never know what might have happened had he not, but it’s conceivable the greatest French cyclist in history may have retired aged just 22. Instead he won the stage, despite his misadventures, by 1’20”. He then repelled a rampant Thévenet in the time trial to complete a famous victory. Business as usual…

Hinault was a megastar in the making, but also a feisty so-and-so to boot. He told Renault he wasn’t ready for the Tour, and refused point blank to ride it. As such Guimard was left in no doubt about where the balance of power lay within the team. That taken care of, he came back in the spring and dominated the Vuelta, and his form since had been mightily impressive. He was ready to go.

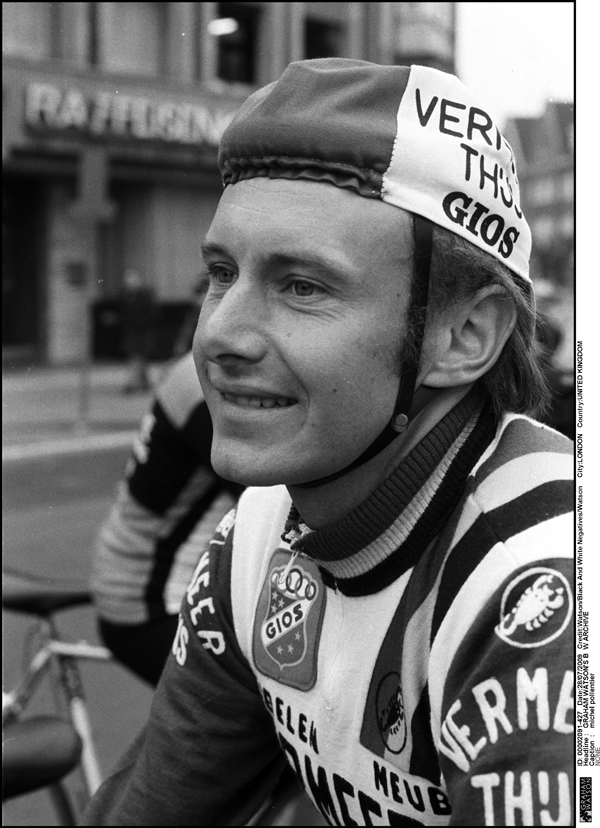

Second favourite would be one Michel Pollentier. He would ride the Tour for the bike manufacturer Flandria, to all intents and purposes a Flemish national team. Short and prematurely bald, Pollentier was in many respects the West Flandrian archetype, a Belgian anti-hero. For all that he was apparently fluent in four languages, wasn’t much given to communicating with other humans, cycling journalist types in particular. Aged 27 now, he’d spent most of his career fetching and carrying for his close friend Freddy Maertens, the best sprinter on the planet. Quiet, diligent and totally without pretence, Pollentier was the perfect domestique. He was appallingly ungainly on a bike, his torso seemingly fixed at 1 o’clock. Somehow though he climbed superbly and, because he could churn huge gears, rode a cracking time trial.

The problem with Pollentier was that, quite frankly, he wasn’t much interested in winning bike races. He was doing very well for himself ploughing Maertens’ furrows, simply because Maertens won so often. When, however, Freddy had crashed out of the previous year’s Giro, Pollentier had been presented with a problem. Maertens’ abandon had Flandria (and by extension the Belgian TV crews) ready to ship out en-masse, not at all good news for the prestige and marketability of the event. Race Director Vincenzo Torriani had therefore gone cap-in-hand to Lomme Driessens, Pollentier’s DS, pleading with him to see the thing through. Driessens told Pollentier that this represented his big chance, but Pollentier said he couldn’t because his wife was about to go into labour, and anyway he had sunstroke. Driessens said he’d never heard anything so ridiculous in his life, and instructed him to get on with it. Pollentier was thus compelled to ride for the GC and, to general bemusement (not least his own) won the thing at a canter.

Asked by an Italian journalist who he’d be riding for the following season, Pollentier said he’d be working, as ever, for Maertens. He’d been doing precisely that since he was sixteen, and saw no reason to change now. The hack, assuming he’d misunderstood the question, rephrased it. When he informed Pollentier that as winner of the Giro he could name his price, he simply shrugged his shoulders. He reiterated that he was a domestique for Fred, and that was that. Weird…

With Maertens absent he then went and won the Tour de Suisse, presumably quite by accident again. He busted his collarbone – for the seventh time – at the worlds in Venezuela, but since then he’d pretty much kept on where he left off in Milan. At the Dauphiné he’d been in a league of his own, winning two stages and, by a bewildering margin, the maillot jaune. The ugliest cyclist in the peloton, the one who’d spent his entire cycling life in the service of fast Freddy, had become the most accomplished rider in the world. How could that happen?

The drama began on stage four, a team time trial over 153 (yes, that’s right, 153) bruising northern kilometres between Evraux and Caen. Pollentier crashed heavily, damaging both shoulder and elbow. Nursed home by his Flandria teammates, he’d nevertheless concede seven minutes to the dangerous Hennie Kuiper’s Ti-Raleigh outfit. Four days later he came to grief again. In another contre-la-montre, this one individual, he’d puncture and lose a minute as the mechanics bungled. He recovered to third on the stage, but still trailed Hinault by two minutes as they reached the Pyrenees.

Stage eleven saw them tackle Tourmalet, Aspin and St Lary, three authentic behemoths. Here it was that the phony war ended. Hinault and Pollentier, clearly the strongmen, grappled for second behind Mariano Martinez, the French polka dot jersey. It was gripping stuff, but ultimately little more than a prelude to one of the most bizarre weeks in Tour de France history.

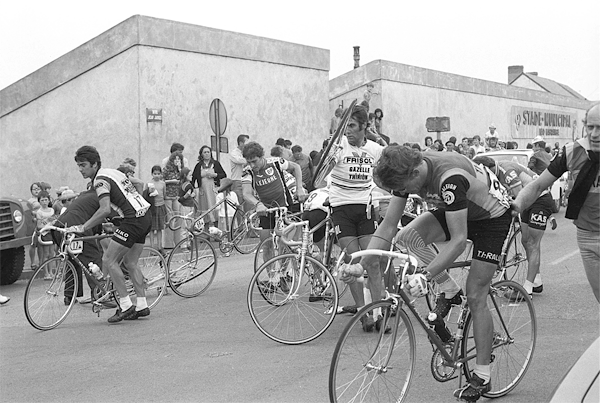

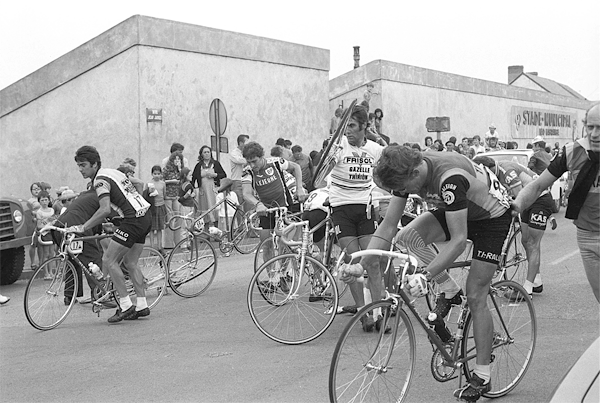

Ski-lifted off the mountain, the riders showered at St Lary’s municipal swimming pool, before climbing aboard the five waiting coaches. From here they were to be driven to Tarbes, some 50 miles due north through cloying traffic. And it was here, in a turgid French traffic jam, where the Tour started to unravel…

As it dawned on them that their one-hour bus journey would take three, 100 or so fractious riders began to grumble amongst themselves. Hungry and spent after a monumental days climbing, they wouldn’t be fed and massaged before 10 o’clock, the poor water carriers much later still. That in itself was pretty woeful, but worse still the following day would see a split stage. They were expected to ride 146km to Valence D’Agen, with the roll-out slated for 7.30. In a practical sense they’d need to be eating breakfast before 5 o’clock, utter madness given this current state of affairs. Worse still, they’d a further 96km to Toulouse in the afternoon, topped off by a 200km train journey to Figeac. From there they’d endure a 221km climbing marathon to Super Besse…

Everybody agreed that split stages were good for business. For Felix Lévitan, the race’s bean counter and co-organiser, they were money for jam. He was able to charge small towns like Valence a very tidy premium indeed for the glamour his travelling circus bestowed. They would stump up not only for a stage finish, but also the afternoon departure. For that they got 100% hotel occupancy and, for one day at least, a chance to showcase their town to millions of sports fans. For the riders too, days like these made sense. Two stages in one day equalled primes, more points, more chances to earn. Sure it was tough for them, but they were cyclists; tough was the business they were in.

Big days on the bike weren’t an issue for cyclists; you don’t sign up for the Tour de France expecting a jolly. This, however, was sheer lunacy – Lévitan was taking liberties and Hinault, self-appointed shop steward, wasn’t having it. He got round the heads of the peloton and organised a go-slow. They rode the stage as tourists and then, 100 metres from the line, climbed off and walked over the finish line; stage annulled. The mayor of Valence, for whom this day had been six months in the planning, was very far from pleased. They offered him a post-Tour crit’, and then his money back, but he was having none of it. He and Hinault were seen to lay hands on one another and, though they never quite came to blows as such, it was a close-run thing. It was all very unseemly, and it served to further to Hinault’s reputation as a bit of a fruitcake. It was a truly extraordinary sequence of events, but it would little more than a prelude one of the more grizzly tales in Tour de France history.

On Sunday 16 July 1978, stage sixteen of the 75th Tour de France rolled out of St Etienne. It would acquaint its protagonists with pain immediately, with a 12km heave up the Col de la Republique. Then, following the 1st category Luitel, it would reach L’Alpe d’Huez, for a grandstand finish. At 240km it would be another monumental day, and in all probability it would decide the race. Jos Bruyere wore the Maillot Jaune, but could no more retain it today than climb Mount Everest. Joop Zoetemelk lay second, 47 seconds in advance of Hinault. Michel Pollentier was third, a further 47 seconds in arrears, and the rest were out of sight.

Two hundred metres from the top of the Luitel, with Bruyere shelled out, Pollentier made his move. He gunned the descent, time trialled through the valley, reaching the bottom of the Alpe with two minutes in hand. Before a huge crowd Zoetemelk, Hinault and Kuiper give chase, but to no avail. This was fabulous, swashbuckling stuff, and Pollentier’s brilliance and bravery saw him add the Yellow Jersey to the Pink of the Giro.

Upon receipt of the jersey, Pollentier was apparently seen riding off towards the team hotel, before returning to present himself at anti-doping. There he was joined by French rider Antoine Gutierrez. UCI protocol provided that, in giving the sample, the riders lowered their shorts and lifted their jerseys. Only nobody in cycling much bothered with protocol. Rather, the unwritten rule was that the poor riders, exhausted from a big day, would simply pee into a flask and be sent on their way. Only today something went terribly, terribly wrong…

Cyclists had been dodging dope controls for a decade or so now. The oldest trick in the book was filling a small, pear-shaped rubber ‘receptacle’ with some good, honest pee, then conceal it out of sight under your armpit. Connected to it was a thin plastic tube, taped down the back and emerging under the scrotum. The technique was straightforward enough – you simply squeezed your arm against your side (think chicken), and the pee was released.

Only Gutierrez’s plumbing was, so to speak, up the spout. He was caught in flagrante, shaking the tube about in a desperate attempt to unblock it. The doping control officer, a local bloke new to this cycling lark, was outraged that an athlete of the Tour de France, the greatest, most noble sporting institution on the planet, was trying to commit a felony. So livid was he that he marched over to Pollentier, in the opposite corner of the trailer, and yanked down his shorts! And guess what? The same thing! They were all at it!

When the dust finally settled Pollentier, relieved of his chemistry set, duly produced his sample and thought nothing more of it. He’d finished the stage at ten past four, and it was 6.55pm when he started to bimble back to the hotel. There, bold as brass, he and roommate Maertens celebrated the Yellow Jersey with a glass of champagne. Only much later, during dinner, did it emerge that he was to be suspended for two months with immediate effect. Thus, sensationally, he became the first rider to be expelled from the Tour whilst wearing Yellow. Asked why he’d tried to cheat, he produced a corker, “I was trying so hard on the Alpe that I peed myself. That’s why I couldn’t produce a sample…”

And so it was that his name became synonymous with doping, the living embodiment of sleaze. Pollentier, a Giro winner and Belgian champion, was pilloried for having besmirched the good name of the Tour, and of cyclists. All right and good, only hang on just a minute…

As he pointed out in a plea for clemency sent to Lévitan and Jacques Goddard, he’d been booted off without having failed a dope test. Nor had he committed a fraudulent act as such, rather he’d simply been attempting so to do. Further, he assured them, he was no more guilty of doping than any number of his peers.

And in truth he had a very, very good point. A Spaniard, Pedro Vilardebo, had been guilty of precisely the same misdemeanour at the Dauphiné just a month previously, and yet he was there, riding the Tour. Everybody in cycling knew that the doping rules were very seldom enforced. Had they been, Pollentier himself would have been positive at the Giro, and also a few days earlier at the top of the Puy de Dome. It was common knowledge that Bernard Thévenet had been extremely positive for ephedrine in winning the Tour the previous year. Equally Gutierrez, whose dicky plumbing had predicated Pollentier’s strip search in the first instance, carried on his merry way. So too did another Spaniard, a domestique named Jose Nazabal. He returned a positive test after the stage, but was let off with a ten-minute penalty which mattered not a jot. The likes of Nazabal, already over half an hour in arrears, were riding simply to get round. Why, then, the double standard?

The Belgian media (and in truth most people around the Tour) were unequivocal; Pollentier had been a victim of French jingoism. Of course what he’d done was shameful, but he’d ridden spectacularly, and cycling was a sport of stealth as well as strength.

We’ll never know quite how many got away with similar tricks back in the day, though it’s been suggested there were upward of twenty at that Tour alone. We’ll never know how many positive tests were buried under the altar of expedience, or whether Bernard Hinault, winner of the 1978 Tour de France, was riding clean. One thing, though, is abundantly clear – French Tour winners always were very, very good for business…

THROUGH THE STORM

Michel Pollentier’s Flandria team would fold following the scandal, forcing him and Freddy Maertens to go their separate ways. Pollentier would ride the Tour again the following year, and would continue riding until 1984. He would add a Tour of Flanders to his palmares, and would twice podium at the Vuelta. Upon his retirement from cycling, he booked into a clinic and underwent a detox program. He obliquely stated that, “It’s impossible to come out of that life without certain psychological and physical problems.” Upon retirement he opened a tyre business, and later a cycling school. He has never named names, and accepts full responsibility for what he did. He maintains, however, that he was the rightful winner that fateful day on Alpe d’Huez.