Itching powder, trains, The Badger, The Cannibal. Tim Moore, author of ‘French Revolutions’ gives us a tour of the classic characters in the history of Le Tour.

Glamorous, tawdry, captivating, capricious. The Tour de France is the only sporting event with its own personality. A bundle of very Gallic contradictions of the sort that inspired Charles Aznavour to write ‘She’. The Tour is a beauty and a beast, a famine and a feast. A neat amalgamation of the disparate characters who have shaped the event, and an even neater example of the portentous gibberish it has dependably inspired for 105 years.

In the Beginning

Born in Italy, raised in France and blooded in Belgium, the 1903 inaugural Tour winner, Maurice Garin, represented the three nations who would dominate the event right up to the 1990s, when some Spaniard won it five times on the trot. The stubby and grandly moustachioed Garin embodied the core attributes necessary to win in that pioneering era. The determination and stamina to keep going when the daily challenge probed the limits of human endurance and the cheery willingness to cheat your filthy woollen shorts off when it went beyond them. Those early Tours were substantially more appalling than today’s. They were leg melting, soul crushing marathons ridden on unmade roads and single speed butcher’s bikes, with stages routinely topping 450km. Competitors were required to carry their own spares, affect their own repairs and feed and water themselves as best they could. The threadbare organisational infrastructure didn’t make life any easier, except when you didn’t want to be seen nicking all the ink from a control point, thus preventing your fellow competitors from signing in. It didn’t prevent you tying a wire round a cork, popping it in your mouth and lashing the other end to an accomplice’s car for a tow across Provence. Or creeping about the hotel at night to sprinkle itching powder down a rival’s shorts and hacksaw halfway through his seat post. Maurice may have done any or all of these en route to his 1903 win. But he upped his game the following year, in a race so disfigured by dishonesty that nine of the 88 competitors had already been expelled by the time Garin rolled into Paris an hour ahead of his closest rival. A whispering campaign blossomed into an inquiry and five months later Maurice Garin, along with the next three finishers and the winners of every stage, was disqualified. No details were ever released as all documentation was lost in the war. But Maurice’s principal offence appears to have been the unimaginative, but devastatingly effective ruse of tackling some of the more challenging stages by train. For this he was stripped of his title and banned for two years. One can only speculate on the chicaneries that led to some of the others being banned for life. A rider in Garin’s position today would have indignantly protested his innocence, mounted a series of dignity sapping appeals, then bitterly shopped every one of his rivals after the last of these had failed. But Maurice, though aware that at 34, the ban effectively ended his career, calmly took the rap. He kept his peace and went back home to Lens, where he opened a garage and went through three wives. Only senility loosened his tongue. In later life he was often found roaming the streets in a poignant search for ‘le controle’, and he’s said to have confirmed the details of ‘Operation Choo-Choo’ to a boy who now tends the cemetery where Maurice Garin is buried.

Eugene Christophe and his Broken Forks

Untarnished Tour heroes were as hard to find back in the early days as they are now, but you won’t read a bad word about Eugene Christophe. ‘Le vieux Gaulois’ is in some ways the ultimate Tour legend. He was the first rider to wear the yellow jersey when it was introduced in 1919 and his record 315km solo breakaway in the 1912 Tour will only be challenged if Caligula comes back from the grave to take charge of the route planning. He entered his first Tour in 1906 and his last, finishing 18th, at the age of 40, in 1925. Along the way he suffered misfortunes that would have driven lesser men to suicide, murder or the nearest railway station. That epic 1912 escape made Christophe a marked man. His Belgian rivals ganged up on him so diligently throughout the remaining stages that halfway through the last he sat up in exasperation, surrendering the chance of overall victory. It’s the same story in 1913, until the race hits the Pyrenees. Halfway up the Tourmalet, the race leader throws in the towel, and Christophe finds himself wearing yellow (or as it was then grey), on the road. One superlative effort and overall victory is all but his. He’s already coasting down the other side of Europe’s highest road, when a race marshal’s car sideswipes him, pitching Eugene into a wall of scree. He picks himself up, luckily nothing broken.

Oh, except his front forks. Mindful of the regulations preventing outside assistance, and drawing upon his experience as the reigning French Cyclocross champion, Eugene shoulders his cast-iron mount and slips, slides and rolls 10 kilometres into the nearest village. There he staggers breathless into the local forge, followed by hawk-eyed, grim-faced Tour snoops, who watch as he single-handedly hammers away at strips of glowing metal. When at last the work is done he’s four hours down. But as he tearfully remounts, a Tour official steps forward. In allowing the seven year old blacksmith’s boy to pump the bellows, he explains, Christophe has accepted indirect third party help. He receives a further 10 minute penalty. Eugene’s unfortunate place in Tour history is assured before he pedals away. But just for good measure, mechanical failures would deprive him of likely victory in two further Tours. In 1919, his forks broke. Then in 1922, his forks broke. He probably ate with a spoon for the rest of his days.

The Gino and Fausto Show

Gino Bartali, the second Italian to win the Tour, was perhaps the last of the old school champions. Fausto Coppi, the third, was first of a new breed. Gino’s 1948 victory, coming a record 10 years after his first Tour triumph, was achieved using a daft lever operated derailleur system, which required the rider to effectively detach the rear wheel, on the move, before each gear change. A year later, Fausto won, with a precursor of the more obvious and substantially less hazardous cable based set up still in use today. Gino refuelled with Parma ham and Valpolicella vino. He kept in shape by tying a heavy trailer to his back wheel and hauling it up mountains. Fausto started the day with fruit and vegetable juice, ate nothing but liver and wheat germ once a week, and pioneered the tapered training system.

The press built up the Bartali/Coppi rivalry, portraying their epic duel in the 1949 Tour as the embodiment of comradely sportsmanship. Here’s Gino waiting for Fausto to catch up after a puncture. See Fausto letting Gino win on his birthday, the two of them sharing a bidon on a broiled ascent of the Aubisque. The reality was rather more fun. Groomed, devout and prudish, Gino was always uncomfortable with the scruffy, swearing and morally lax Fausto, who later went on trial for adultery. Those really were the days. Coppi’s married mistress was briefly imprisoned and the Pope expressed his revulsion by refusing to bless the Giro peloton in defiance of long-standing tradition. When Fausto, five years his junior, began to defeat him on a regular basis, Gino’s haughty disapproval blossomed into twitching obsession. Through scarily intensive observation, he came to note that a particular vein in the crook of Coppi’s right knee would swell when his lanky rival was in trouble. Thereafter, he routinely delegated a team-mate to monitor the lower leg in question. Fausto must have spent long days in the saddle wondering if he’d stepped in something.

What got Gino’s veins fit to bust, though, was his conviction that Coppi’s victories were achieved with narcotic assistance rather more effective than that prescribed by his own doctor which was three cigarettes a day, to counteract a low heart rate. Bartali once drove 150 km through the night to retrieve a suspect flask he’d seen Coppi discard. The analysis turned up nothing racier than bicarbonate of soda. His embittered paranoia would peak during grand tours, when in the kind of swivel-eyed, giggling derangement associated with Inspector Clouseau’s boss; he’d sneak into Coppi’s hotel room while Fausto was at breakfast, emptying bins and rifling through drawers in a fruitless quest for incriminating pharmaceutical evidence.

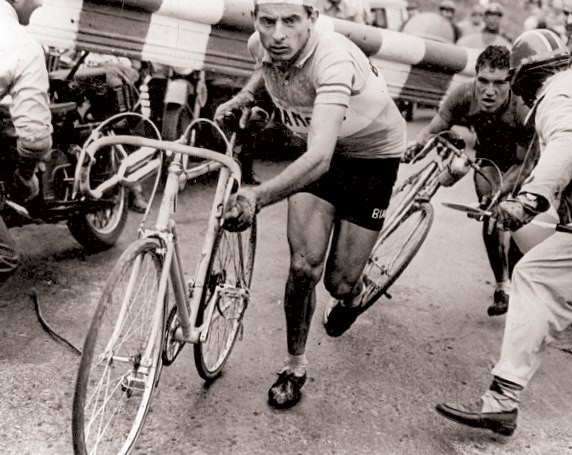

In retirement he came to hate himself for the unkind thoughts that inspired this behaviour. In his darkest phase, he was sniffing Coppi’s suppositories and he begged forgiveness. “So innocent, so pure. How could I have doubted you?” Fausto nobly accepted the apology, waiting until his own career was over before cheerily confessing to having used Fausto Coppi goes below the barrier. Gino Bartali, the paranoid champion amphetamines “when it was absolutely necessary”. And how often was that? “Almost always.”

Dying very shortly afterwards spared him Gino’s outraged splutters, though Bartali had the last laugh. Asked in old age to reminisce on the iconic 1949 photo of the pair sharing a drink as they slogged up the Aubisque side by side, Gino generously recalled “letting my good friend refresh himself from my supply”. In truth, Coppi had just caught Bartali, and handed over his own bottle before disappearing up the road. “Here you go – finish it,” he said. By the end of the stage he’d taken three and a half minutes out of his toiling compatriot, and 10 days later Coppi rolled into Paris to claim victory. It’s hard not to sympathise with Gino Bartali’s noble determination to win clean, yet it’s just as hard not to feel a certain respect for the Tour’s many brazenly defiant self-medicators. “You want to see how we keep going, huh?” said 1923 Tour winner Henri Pelissier to a curious journalist, before tipping a bag of ampoules and bottles on to the table. “Cocaine for the eyes, chloroform for the gums. And then there are the pills…” Jacques Anquetil, the dominant Tour rider of the late Fifties and early Sixties, was outstandingly candid on the issue. “Only a fool imagines it’s possible to do these things on just water,” he told one reporter. When that proved too runic a response he added succinctly, “Everybody takes dope.”