The Cannibal

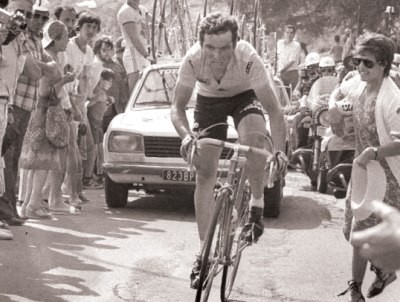

Charisma, good grace and perhaps a certain sexual allure are prerequisites for your typical sporting legend. Eddy Merckx had none of them, but then road cycling is not your typical sport. The Tour de France is about taking on a physical challenge that’s like something out of Greek mythology, despatching your rivals along the way with an iron willed brutality of similar derivation. Anquetil set the template for the ruthless professionalism that has come to define the modern Tour, but Merckx perfected it. Here was a blank eyed, baby faced assassin whose catchphrase, which he learned to say in five languages, was the clunky but compelling “I am completely indifferent.” A cycling machine who coldly noted that though there were limits on any rider’s physical capabilities, “there are no laws that govern the will”. He is a Belgian who until recent criminal history was surely the scariest Belgian of all time.

The Tour is a battle, a struggle to the death against gravity, the elements and human frailty. It’s bad enough already without the participants fighting amongst themselves, which is perhaps why fans and chroniclers have always felt uncomfortable pitching the event’s chief protagonists on opposite sides. It’s far more romantic, more noble and definitely more French, to mythologise Tour competitors as comrades in arms, a band of brothers bound together by mutual respect, chivalry and a doughty belief that the honour of simply taking part outranks any grubby desire to win. They did it with Coppi and Bartali, and with Anquetil and Raymond Poulidor, the most famous bridesmaid in Tour history. Though you might want to check how that translates before saying it to his face. But they could never do it with Eddy. Calculating and single-minded, Anquetil was nicknamed ‘The Lawyer’. But even he adhered to the hallowed tradition in which a team leader rewarded loyal deputies by granting them a stage victory or minor jersey. Merckx had no time for any of that rubbish, and was quickly dubbed the Cannibal.

Eddy never did just enough to win. His victory in his debut 1969 Tour remains a masterclass in crushing, heartless domination. He wound up with all three jerseys, the only man ever to have done so. At just 24 years of age, he’d also have bagged the young rider’s jersey had it then existed. His stupendous winning margin of nearly 18 minutes, a throwback to the Coppi era, may never be bettered. Lance Armstrong couldn’t beat anyone by even half that. The year after, he won nine stages, another feat we’re unlikely to see repeated. In the 1971 Tour, finding himself in the unfamiliar overall position of second, Eddy led 200 hangers-on into Marseilles so far ahead of schedule, (250km at an average speed of over 45 kph), that no one was there to greet them. By the time Mayor Gaston Deferre turned up to present the prizes, Eddy and co were in the shower back at their hotels. Deferre could have taken this humiliation badly, but being French he merely vowed that the Tour would only return to Marseilles over his dead body. Interestingly, after 27 consecutive visits up to 1971 the race next visited Marseilles in 1989, three years after Gaston’s last gasp. Oh, and Eddy went on to win that Tour by nearly 10 minutes. Ruthless when in front, terrifyingly determined when he wasn’t, Eddy was the relentless bastard’s relentless bastard.

Two weeks into the 1975 Tour, Merckx lost his lead after a slightly mad old man punched him in the kidneys as he climbed the Puy de Dome. A couple of days later, he broke his cheekbone and jaw in a crash that left him eating through a straw and unable to talk. At a rather one-sided press conference, Tour hardened journalists begged him to retire. He didn’t, of course, and on the run in to Paris, defied perhaps the most irksome Tour tradition of all by attacking the race leader on the last stage. The peloton eventually reeled him in, but he still took second place in all three classifications.

The Badger

Eddy, inscrutable to a fault, let his bike do the talking. Bernard Hainault, the angriest man in Tour history, would sometimes delegate that job to his fists. Hainault’s default demeanour on a bike suggested he’d just been told that some bloke up the road was prancing around in a wedding dress singing “Bernard, Bernard, je m’appelle Bernard!” “As long as I breathe, I attack,” he once said. This was bad news for his rivals and indeed for the protesting shipyard workers who made the mistake of standing across the road when Bernard Hainault was in the lead. Because it was only the Paris- Nice race, he let them off with a few right hooks. If it had been the Tour, somebody would have been puréed. Mad Bernie was fuelled by a monstrous, hors catégorie ego. He was a bad loser and an absolutely insufferable winner. “It’s said that a great victory doesn’t really sink in until afterwards,” he writes in his autobiography, recalling a world championship triumph in 1980. “Not in my case! I knew straight away what I’d done. I had conquered everybody.” Hinault never did favours, even to those wearing the same jersey. His Tour tussles with Greg LeMond invariably describe the American as his ‘ostensible teammate’. In 1985, LeMond was denied a shot at overall victory when Hinault, flagging many minutes behind in an Alpine stage, got the team management to tell Greg he was only seconds back. LeMond sat up.A year later, Hinault attacked LeMond, now his team leader, all through the mountains, insisting he was doing so “to demoralise the opposition”.

The excuse wore thin when he was still at it with Paris almost in sight. “It was rotten being on that team,” recalls Andy Hampsten. “Steve Bauer and I had to chase down Hinault on the stage into St Etienne. That really sucked.” They don’t make Frenchmen like that anymore, which may explain why no native has won the Tour in the post-Hinault era. LeMond aside, Hinault was the last great champion before the age of the team doctor. It’s hard to imagine Lance Armstrong having his bidon filled with champagne on the last climb of the day, as Bernard did, or quitting a team over an argument about how much wine he was allowed at dinner. With all that’s gone on over recent years, it’s difficult to muster any great affection for the riders who now head the ‘classement général’.

“These days, the true keepers of the Tour flame are back down the wrong end of the peloton. Men like Jacky Durand, the bandana-clad loose cannon whose Tour speciality was the heroic but doomed lone breakaway.”

“I Either Win or Lose”

Throughout the late 1990s, the sight of a wobbling Jacky being swallowed up by the pack with the line almost in sight became a hallowed Tour tradition. Heartbreaking to the viewer, perhaps, but never the man himself: “I either win or lose,” he said. “Nothing in between”. A mission statement deftly encapsulated in 1999, when Jacky achieved the unique distinction of claiming both the combativity award and the lanterne rouge, as the Tour’s last place finisher. Three years later, Jacky’s last Tour ended with a disqualification secured in the event’s finest tradition: he was caught being towed uphill by a team car. Maurice Garin would have been a proud man. And so too might Arsène Millocheau, lanterne rouge in that first Tour, who creaked into Paris nearly 65 hours down on Garin, and never rode a bicycle again.