Paris-Roubaix, France’s great cycling anachronism, was once a symbol of modernity. Herbie Sykes examines the origins of the Hell of the North.

Paris-Roubaix, France’s great cycling anachronism, was once a symbol of modernity. Herbie Sykes examines the origins of the Hell of the North.

By the mid-1890s, 100 years on from the revolution, France was finally being re-invented. The so-called ‘mission civilisatrice’ pledged finally to deliver liberty, equality and fraternity. This new France would be a secular meritocracy and would deliver free (and compulsory) schooling, national service and accessible healthcare. A burgeoning rail network linked Marseille to Calais, whilst the ‘Dreyfus affair’, the biggest scandal of the century, enveloped all of France. In Paris a group of influential liberals mobilised in support of a Jewish army captain wrongly imprisoned for treason. Led by the great writer Émile Zola, they became known as ‘intellectuals’, a pejorative new term in the French lexicon.

The capital also saw completion of the much vaunted “tallest structure in the world”, on the Champ de Mars. All agreed that it was big and obscenely expensive, and doubtless it represented a monumental feat of engineering. The problem was that it was hideously ostentatious, not to mention pig-ugly. The great architect Charles Garnier described it as “a hideous black shadow besmirching the city”, whilst Guy de Maupassant, when asked why he took lunch every day in its restaurant, opined that it was the only place in the city where he didn’t have to look at it.

Meanwhile the so-called ‘safety bicycle’, with its wheels equal in diameter, played its part. Increasingly affordable and increasingly egalitarian, it was the status symbol, delivering free-of-charge DIY travel to the lower-middle classes, if not yet quite to the great unwashed. As prices plummeted, bikes were used to ferry the sick, to fight fire, to deliver goods. Even bicycle regiments were formed, whilst something called a ‘Dynamo’, a kinetic energy-powered marvel, facilitated night riding. Simply by pedalling, the rider generated enough wattage to light the road ahead. Who’d have thought it?

Track cycle racing – the fastest thing most Frenchmen had ever clapped eyes on – won hearts and minds the length and breadth of the land. New velodromes sprung up almost weekly, a badge of honour and a mark of sophistication for cloying local politicians. Any progressive town, it seemed, needed a track, or more precisely, needed to be seen to have one. With them came a new breed, the professional cyclist. They ushered in a plethora of new racing disciplines, whilst their bikes were the subject of one dizzying innovation after another. Lighter frames, more robust wheels, efficient new brakes…

Track cycling’s pre-eminence had always conditioned road racing, its delinquent cousin. The track was all about dazzling speed, about balance and immediacy. Its great virtues were its absolutism, and the fact that it provided perfect publicity and sponsorship opportunities. Audiences at the velodromes were captive, and as such perfect for advertisers in the pre-electronic age. The road, on the other hand, offered none of the above, and so in order to fire the public imagination race promoters had resorted pretty much to masochism. Their races increasingly tended towards epics, based around unthinkable human sufferance. Run over callous distances, their fields were in the main comprised of failed or retired track riders, those not good enough to earn the decent livelihood the track could bestow. So ruinous was the sheer physical effort required that those who competed were considered lunatics. Whilst the rapiers of the track were regarded as dashing, urbane and glamorous, the attraction of the roadie (such as it was) was strictly of the fairground variety. Only an imbecile, most concurred, would begin to contemplate a life doing what they did.

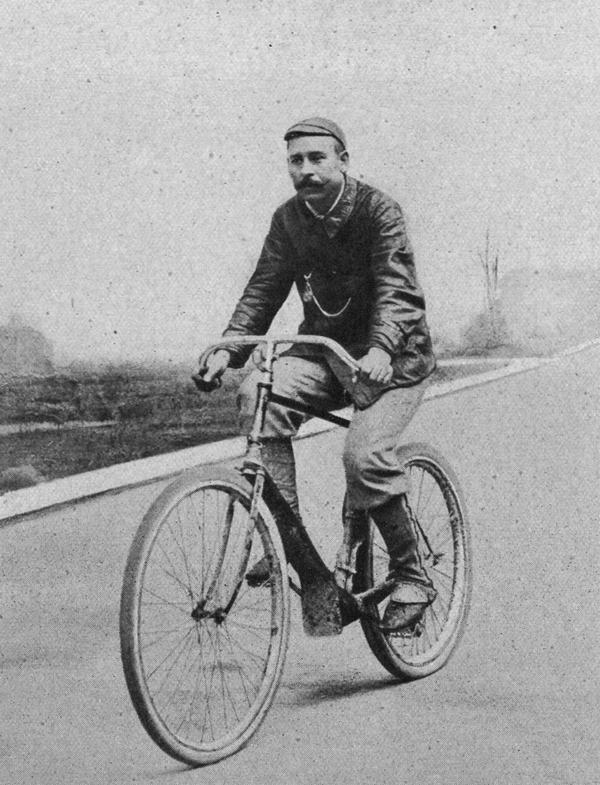

Bordeaux-Paris, a mammoth 600km uphill and down dale northwards odyssey, had established itself as French road cycling’s biggest race. In so doing it had supplanted an even bigger folly, the 1200km madness which was Paris-Brest-Paris. The inaugural edition, held in 1891, had been won by the first megastar of French road cycling. The extraordinary Charles (‘Charley’) Terront had been engaged by the Michelin rubber company to test their latest prototype, a replaceable pneumatic tyre. Terront had triumphed with a bravura performance, on a bike weighing 21.5kg. Rattling round in twenty minutes shy of three days, he beat runner-up Laval by the thick end of eight hours, as upwards of 10,000 cheered him home. Of the 206 starters 99 made it back within the ten-day time limit – little wonder the race held the French public in its thrall.

Born in Paris’ northern suburbs in 1857, Terront was one extraordinary human being. At the age of just 22 he’d established the 24 hour record, a jaw-dropping 546km. His was a herculean feat of endurance, but in the event it was to be little more than an ouverture. In 1893, two years on from the Paris-Brest-Paris exploit, he saw his 24 hour record walloped by one the redoubtable Maurice Garin, a French-speaking Italian from the Aosta valley. Garin somehow rode 701km, whereupon Terront took it upon himself to cycle 3000km from (of all places) St. Petersburg to Paris. So outrageous an undertaking was it that he was joined by a phalanx of journalists, as the idea of long-distance bicycling seeped into the public consciousness. Charley achieved the impossible in 14 days, and when he got home the fanfare was so great that he became as the first sportsman to be the subject of a new literary form, the biography.

For all that it lagged behind the track, Paris-Brest-Paris’ success – and Terront’s extraordinary fortitude – had done wonders for the sport’s popularity. Roadies were still considered very much cycling’s underclass, but the discipline was slowly gaining a foothold. Le Vélo, the daily sports paper which owned the big events, needed more races in order to shift more newsprint, and roadmen came cheap by comparison to the dandies of the track.

In February 1896 Théodore Vienne had a bright idea. A wealthy mill owner from the flourishing textile town of Roubaix, he’d built a velodrome the previous year, and it was doing a roaring trade. So fast was the track that they came from nearby Lille to ride, but also from across the Belgian border. Whilst ruminating on the fact that the facility lay idle during the day, he got to thinking about Easter weekend. Why not use it to host the finish of a road race on the Sunday afternoon? That way it would generate additional revenues, and more publicity and prestige for the town itself? If he filled the place with paying customers he could go a good way towards covering the costs, and his business associates would be happy to provide additional sponsorship. The trick would be to put on a show around lunchtime, ergo have the punters make a day of it. Of course they’d be needing sustenance while they waited for the racers, and so with a fair wind he should be able to turn a profit. Logistically and financially he reckoned he could cover most of the bases, but the tricky part would be selling the idea to Le Vélo. He called on his friend and fellow cycling-nut, Maurice Perez, and the two of them put their thinking caps on…

One of the major shortcomings of road racing, they reasoned, was a lack of credibility. Bordeaux-Paris was a great marathon, but it was run over such a prodigious distance that much of it happened at night. Street lighting, another modern wonder, was being rolled out in a few major conurbations, but in the main when it got dark the cyclists had nought but their dynamos. Thus stealth – or cheating, if you will – had become an important weapon in their armoury. Under cover of darkness, all manner of apparently superhuman exploits were performed as racers, seemingly in pieces at dusk, covered gargantuan distances during the night. Many would do so on trains, or secreted in horse drawn carriages. Others simply took shortcuts, but in truth it was impossible to keep track of them all. Checkpoints were installed en-route, but still they ducked and dived, and as such the sport developed a reputation for attracting ne’er-do-wells and charlatans. Where the track was simple to follow, accessible and transparent, road racing was – whichever way you sliced it – just plain… murky.

One of the major shortcomings of road racing, they reasoned, was a lack of credibility. Bordeaux-Paris was a great marathon, but it was run over such a prodigious distance that much of it happened at night. Street lighting, another modern wonder, was being rolled out in a few major conurbations, but in the main when it got dark the cyclists had nought but their dynamos. Thus stealth – or cheating, if you will – had become an important weapon in their armoury. Under cover of darkness, all manner of apparently superhuman exploits were performed as racers, seemingly in pieces at dusk, covered gargantuan distances during the night. Many would do so on trains, or secreted in horse drawn carriages. Others simply took shortcuts, but in truth it was impossible to keep track of them all. Checkpoints were installed en-route, but still they ducked and dived, and as such the sport developed a reputation for attracting ne’er-do-wells and charlatans. Where the track was simple to follow, accessible and transparent, road racing was – whichever way you sliced it – just plain… murky.

Vienne and Perez knew full well that theirs was a provincial town of just 125,000 people, and that nobody would seriously entertain the idea of Roubaix-Roubaix. If, however, the race were to start in the capital, some 280km south, and follow the straight road towards Lille, they reckoned it could be a winner. Of course 280km was barely any distance at all, but according to their sales pitch the race’s brevity would also be its great virtue. It wouldn’t be an odyssey like the others, but rather a punchy affair run exclusively in daylight. There’d be none of the after-dark chicanery which undermined the Bordeaux-Paris, and as a result it would help to rebuild the questionable reputation of road cycling. Finally, they reasoned, they needed to be seen to respect the fact that Bordeaux-Paris was the main event of the season. They’d have to demonstrate that they sought not to usurp it, but to heighten expectation ahead of it. By running Paris-Roubaix a month in advance they’d be doing precisely that, whilst providing a useful training exercise for its aspirants. In short it would be the perfect hors d’oeuvres, a good day out and a useful little earner! Oh, and 1000 francs for the winner, six months wages for a textile factory worker; that ought to convince them…

Paul Rousseau, the boss of Le Vélo, was impressed by the prize money on offer. Of less appeal, though, was the trifling distance, and the idea that it be promoted as a warm-up race for Bordeaux-Paris. Undecided, he despatched the paper’s cycling expert, Victor Breyer, to ride the route. Breyer had a driver drop him at Amiens (roughly half-distance), then set off under a deluge which wouldn’t abate for 48 hours. By the time he reached Roubaix he was beside himself with cold and exhaustion. He grumbled to Vienne it was a “diabolical” idea, but somehow later that night, following a following a meaty slice of Roubaix ‘hospitality’, allowed himself to be persuaded otherwise.

Breyer’s report praised the enthusiasm of the northern people, and the many stretches of asphalt he’d found along the parcors. What was most impressive, though, and most surprising, was the degree to which the roads around Roubaix were cobbled. Pavé demonstrated the wealth of the area because it ensured good, reliable transportation regardless of weather conditions. Cycling on it would be hard, without question, but by the same token 280km wouldn’t unduly trouble the warriors of the road.

All seemed set, until the local clergy cried foul. A bike race? On Easter Sunday? Sacrebleu! Vienne again put his hand in his pocket, said ten Hail Marys. He offered a substantive donation to charitable works and a “mass for all cyclists”, but still it didn’t wash. His race was pushed back a fortnight, but by hook or by crook Paris-Roubaix was up and running.

All seemed set, until the local clergy cried foul. A bike race? On Easter Sunday? Sacrebleu! Vienne again put his hand in his pocket, said ten Hail Marys. He offered a substantive donation to charitable works and a “mass for all cyclists”, but still it didn’t wash. His race was pushed back a fortnight, but by hook or by crook Paris-Roubaix was up and running.

Over 100 signed up, though in the event only 45 made it to the start. Vienne needn’t have worried though. His race, cheered on by vast crowds on a lovely spring afternoon, would be a huge success. The early pace was set by an Englishman, one Arthur Linton. His methodology, like that of all the better prepared riders, was derivative of the lung-busting distances they were expected to cope with. It involved a hand-picked group of helpers, all of them decent cyclists in their own right, strategically placed along the route. They would pilot a tandem (usually for 100km or so) before handing it over to the next couple. The better riders paid more to have the best pacers and tandems, and so the hierarchy was established.

At Amiens, Linton was joined by German hard man and race favourite, Josef Fischer. When Linton’s tandem was brought down by a stray dog, Fischer pushed on alone. Despite running a near-miss with herd of cattle, he romped home in 9’17”, easily defeating the runner-up, a Dane named Meyer. Garin was third, but claimed he’d been sabotaged by Meyer’s pacers. Their tandem, he claimed, had deliberately baulked his as it tried to overtake, and he’d ended up in the ditch as a result.

The race, and the cosmopolitan nature of the competitors, captured the hearts and minds of the northern people. To most the notion that foreigners might ride to Roubaix was indescribably esoteric. The overwhelming majority amongst them had never even seen a German before (or a Dane, or an Italian) and were taken aback that they be in their town. More astonishing still were the speeds at which they rode. That Fischer had thundered from Paris at 31kph was mind-boggling to many, utterly inconceivable to the majority. His arrival at the velodrome created near-pandemonium. So popular was the spectacle that one of the stands, creaking under a heaving mass of delirious fans, collapsed in on itself.

The people of the North had declared themselves impressed, and so Paris-Roubaix was stitched into the French sporting patchwork. The following year Vienne had his way, and over 116 glorious years the race (known locally as ‘La Pasquale’) has become an Easter fixture for cycling fans the world over. As bike racing in general becomes more homogenised, it remains the ultimate test in bike handling, guts, strength and stamina. Truly a modern-day miracle…

The Greatest Show On Earth

Four weeks on from Roubaix another of French cycling’s great survivors, Paris-Tours, would enter the stage. Meanwhile others sprung up in Italy, Germany, Belgium and Switzerland, as road racing bridged the metaphorical gap on the track. Most of them have long since been confined to the dustbin of cycling history but Vienne’s big idea remains, the undisputed highlight of the classics season. Every Easter we are re-acquainted not only with its implacable landscapes and heroic performances, but also, in some way, with Northern Europe’s journey through the 20th century.

These days it rolls out of Compiègne instead of Paris, and the pacers are no more. It eschews the straight road to Lille, but instead flits here and there to locate the 27 remaining stretches of pavé its continued presence preserves. The original velodrome was bulldozed in 1922, the bikes and bikers belong to a different world, but it matters not a jot. The marvel which is Paris-Roubaix, the greatest bicycle race on Earth, is 116 years young…

Welcome to Hell

Victor Breyer, the journalist who first approved the route in 1896, would be instrumental in creating the legend of Roubaix as we know it today. In 1919 he was dispatched with Eugène Christophe, the great French racer, once more to ride the route. They were sent by L’Auto, owners of the race following the demise of Le Vélo, to establish whether the roads were in a fit state to reprise it. Nord (the French department in which Roubaix is situated) was one of the principle theatres of WWI, and in his column Breyer wrote of the desolation the conflict had visited upon the area.

His piece detailed the bomb craters and collapsed mines, the obliterated schools, factories and homes he encountered in the towns and villages along the parcors. He wrote that, “All that remains are the crosses of the fallen, with their red, white and blue ribbons. There isn’t a tree left standing; nothing has been spared. This is hell…”

Breyer’s “enfer du nord”, or Hell of The North, somehow became synonymous with the race itself. These days it’s ubiquitous, and not for nothing is the Roubaix lexicon decorated with war references. Arguably the most famous, most dangerous stretch of pavé is in the Arenberg Forest. It wasn’t actually included until 1968, but still it’s become known as ‘The Trench’.