The bicycle with two same-sized wheels driven by a chain was introduced in the 1880s – it was single speed. Multiple gears came along just after 1900. The first vaguely recognisable derailleur gear system was introduced in 1949 and it heralded a paradigm shift for riding in hilly terrain. I don’t think disc brakes will make the same huge difference that the derailleur did, but I think they will be a major step.

In the 60s cars began to make the swap from drum to disk brakes. Despite the added weight and expense of the disc, they worked so much better it was inevitable that all cars would soon have discs on at least the front wheels. In the 90s it was the turn of mountain bikes to swap from rim brakes (‘V’ brakes and cantilevers) to discs. Just like with cars, the added weight and expense was justified by the much better braking. Now 20 years later it is the road bike’s turn to go through the transformation.

Changing from brakes that grab the rim to ones that grab a dedicated rotor is not a trivial engineering challenge. This article will run through the changes that have to go along with the idea of new, better brakes.

A Short History of Rim Brakes

Rim brakes have been around for over 100 years. It is simple and effective having the rim also be the rotor – and in a road bike this gives us a 622 mm rotor. Brake effectiveness is directly related to rotor diameter and the rim is a large rotor (I’ll come back to this).

Grabbing the rim also places certain restrictions on frame and rim design. Frame and fork have to have certain dimensions because the rim must be located within the distance that the brake pads can adjust in the caliper – around 20 mm in standard road brakes, plus another 12 mm from ‘long’ reach calipers. Any more than this, or to gain room for wider tyres, requires cantilever brakes as seen on touring, cyclocross and older mountain bikes.

The rim itself has to have parallel tracks for the pads to rub on. The tracks have to be strong enough to withstand the crushing application of the pads and thick enough to stand up to the wear that braking causes (and still the rim will wear out eventually). The rim also has to be reasonably true to not rub on the pads.

Enter the disc

Almost everything we are seeing on disc road bikes has been borrowed from mountain biking. That is a good thing because MTB brakes these days are very good indeed. It does require a lot of new parts: hydraulic master cylinder brake lever (which means a different shift unit as they are integrated), hydraulic hose, disc caliper, beefed up fork and frame with caliper mounting points, new hub with rotor mount and a rotor. It also allows you to free the rim shape and add as much or little clearance for the tyres as you want.

Lever

Starting with the lever and working our way down to the hub, let’s consider the parts one by one. Both Shimano and SRAM already have a full range of brake/shift levers with a hydraulic master cylinder inside. For Shimano these cover either mechanical or electronic shifting (in an Ultegra level unit only) and SRAM offers three levels of disc options (Rival, Force and Red). These mount on the handlebar in an identical fashion to older levers.

To join the hydraulic lever to the caliper requires a hose. It doesn’t look too much different to traditional cable housing, and it can be routed around the bike similarly (internally or externally). On installation and periodically (though it may be years in between times) it does require bleeding the air out of the system; quite different to cables.

Caliper

The calipers are available for two attachment methods: post mount (borrowed from mountain bikes, where the bolt goes through the caliper and threads into the frame or fork) or flat mount (new just for road bikes, the bolt is inverted in that it goes through the frame and threads into the caliper – on the fork a thin mounting plate is bolted to the caliper before that plate is attached to the fork). So long as you match the bike and brake mounting type, there will be no problem. Adapters to mount mismatched brakes to frames are also possible.

On a fork the junction of the fork blades and the steerer tube in the crown has to be strong anyway so removing the brake from the crown won’t change things. At the back end the brake bridge required a certain robustness from the seat stays to support the braking forces – so this area can be slimmed down (and the bridge dispensed with completely) for discs. The caliper mounted to the bottom of the left fork blade puts a lot of new load there so the fork has to go to boot camp to beef up before it can support a brake. The forces from the rear brake mean that the left dropout area has to be up to the task as well, but generally it doesn’t look much different than before.

Hub

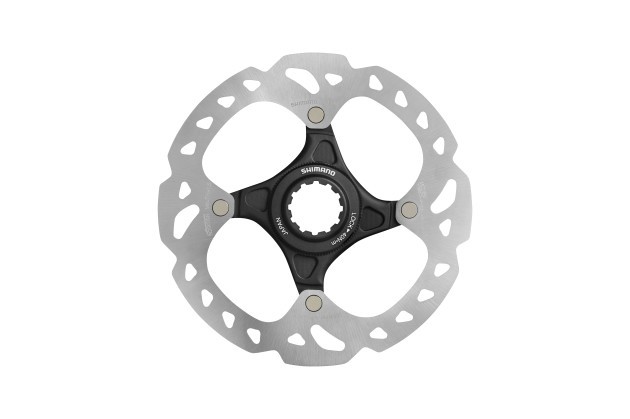

Getting to the hubs we continue to have options. There are two ways to attach the rotor to the hub; centrelock (looks like a cassette lockring holding the rotor onto a splined flange on the hub) or 6-bolt (literally six bolts threaded through the rotor into the hub).

Virtually every current road bike uses standard interchangeable hubs – 100mm front and 130mm rear width using a quick release skewer. Until fairly recently mountain bikes used the same 100mm front hub (but with a disc mount) and a 135mm rear width (with the asymmetry of rear wheels to make room for the cassette, this extra width gave room for the rotor without moving the hub flanges closer together). Recent mountain bikes have moved to a ‘through axle’ at both ends. They are similar to a skewer except they are much larger in diameter and thread into the frame or fork on one end and are then levered shut (like a QR) to hold them in place. Even loose, the wheel is positively retained.

Disc road bikes have almost exclusively chosen to go with the MTB quick release standard (100/135 width), though the Trek Domane pictured has DT Swiss wind up quick release axles as do some cyclocross bikes, but it seems the majority of road bikes are opting for slimmer, perhaps lighter looking options. While some hubs can be switched from quick release to through axle sizes by switching adaptor lugs in the hub and a few minutes of time, most cannot so don’t expect it to be possible. It’s this point that causes much contention in road racing for the provision of neutral service wheels; how can they be expected to carry so many options of axle, rotor and hub?

Rotor

Finally we have the rotor itself. As I mentioned above, rim brakes make for a 622mm rotor. The largest readily available rotors, used on specialist downhill bikes, are 203mm. But road bikes use either 140mm or 160mm rotors. At around ¼ the diameter, they provide only ¼ of the braking force. Hydraulic actuation means that some advantage can be gained back compared to the cable-operated rim brake by converting finger power to retardation, but it’s never going to be equal. My experience suggests it is plenty good enough though. In fact, despite the on-paper advantage rim brakes enjoy, for a long brake-filled descent I would choose disc brakes every time for the light action of the lever (no tired fingers).

Heat

Another issue I have alluded to is heat. Brakes literally turn kinetic energy (forward motion) into heat energy. Putting heat into an alloy rim is fine – the aluminium is an excellent heat conductor and the rim has enough mass to cope with an awful lot of heat. If you are into club racing, gran fondos or even big coffee shop rides you will have noticed that almost everyone these days is sporting carbon fibre rims. Carbon is a great material for making rims that are light and aerodynamic. It is, however, a terrible conductor of heat and if you overheat it the resin will melt, allowing the rim to delaminate (which is terminal for the rim but may also result in the tyre blowing off the rim and the rider crashing). Latest generation rims use high temperature resins and special pads to avoid this excessive heat condition, but it is still possible to overheat a carbon rim by braking. Discs are a great idea for removing the heat from the carbon rim.

With finned brake pads passing heat to the air and Freeza rotors doing the same (Freeza has an aluminium layer sandwiched between two steel layers with the aluminium portion extending inwards to form a finned heat sink), Shimano can specify 140 mm rotors as the standard for their system and know that the brakes will cope with almost anything you can throw at them. SRAM specify 160 mm rotors as their standard size because the extra size gives their fin-free brakes the heat capacity they require. Of course wheels with different rotor sizes installed cannot be swapped.

Spokes

There is one more essential change to complete our braking transformation. Almost every current front wheel from the least expensive to the most exotic employs radial spokes. But you will never see a rear wheel with full radial lacing. The reason for this difference is the drive force transmitted from the hub to the tyre in the rear wheel is via the spokes. If they aren’t laced in a crossing pattern they cannot drive the bike forwards. Putting the brake rotor on the hub means that the retardation forces have to be transmitted from the hub to the tyre via the spokes in exactly the same manner – so disc wheels front and rear must have crossed spokes.

I really believe that in about a decade we will all use disc brakes on our road bikes without issue. The transition period creates problems of old gear not working with new gear, sheds full of really nice legacy wheels that can’t be used, mechanics learning new skills–and there’s always the fear of the unknown for everyone involved. Embrace the disc–it’s both inevitable and better.