Three Hors Category climbs over 210km, finishing at Alpe D’Huez. Matt Hart gives us an insight on how the Tour riders will fuel for such a formidable stage.

You don’t need me to tell you that the Tour de France is a hard race. That would be a bit like telling an English cricketer that his teams got bugger all chance of beating the Aussies. It’s historically obvious, with an extremely slim chance of the situation ever changing. I’m allowed to say these things though. I’m English with a disdain for cricket. So as far as I’m concerned, you can keep the game and all the others that you’re better at than us for that matter. Being European (when it’s convenient) though, I do live in much closer proximity to the most famous cycle race in the world than you. We even started the race last year. So somehow that makes me feel quite smug and superior in my own little way. It’s not an admirable trait and not one that I’m proud of, but it makes me feel better. Now I’m ready to do the serious bit (the bit I’m paid for).

Stage 17 of the Tour de France is a formidable challenge, starting in Embrun at 911m altitude and taking in the Col du Galibier (2645m), the Col de la Croix-de-Fer (2067m) and finishing at L’Alpe D’Huez (1860m). The stage is 210 km long, it’s bound to be extremely hot and the riders are climbing to altitudes where oxygen is a little harder to get hold of. What on earth does a Tour rider have to feed himself with to get through this gruelling stage? It’s not just a gruelling stage actually, it’s a gruelling stage which follows another not quite so taxing stage (Cuneo to Jausiers – 157Km), but one that’s still quite arduous none the less!

Dr Asker Jeukendrup is one of a handful of highly esteemed researchers and authors on Cycling Science. In his book High Performance Cycling he says, “Cycling is among the sports with the highest reported daily energy expenditures.

The levels of energy expenditure have been measured and estimated with various techniques. One of the methods often used is the doubly labelled water method, an accurate technique that allows measurements of energy expenditure over longer periods (days). This method has been used in races such as the Tour de France to measure the amount of energy the riders expend each day. During the three weeks of the Tour de France, the riders expend an average of about 25 mega joules (6,500 kilocalories per day) with extremes up to 36 mega joules (9,000 kilocalories).” Data from Floyd Landis’ Powertap measuring system during a similar stage of the 2006 Tour backs this up. Although he burnt 5,456 kilocalories (kcals) on the bike, when you take into account his resting metabolic rate, it’s not going to be far off the daily energy expenditure figures quoted by Jeukendrup. A heavier rider will also burn more calories than a lighter rider, so all things considered; I think it would be reasonable to assume that Stage 17 of this year’s Tour is going to elicit a calorie burn somewhere in the region of 9,000 kcals per rider. How much is this? Well, if you consider that fat has nine kcals per gram, then this amounts to a kg of solid fat. Can you imagine holding a kilogram of solid fat?

When you further consider that both carbohydrate and protein possess only four kcals per gram, we’re talking well over two kg worth of these two nutrients. This still doesn’t put it into perspective really, because accompanying practically all foodstuffs there is something called dietary fibre. This helps to move waste through the bowels, but is metabolically useless and extremely bulky. So, in real food weight terms, we’re probably looking at close to three kg of ‘dry food’. Yes, this doesn’t include the water that’s inherent in all food, just the calories and fibre. So 9,000 kcals is a lot of food. Asker goes on to say: “When we express daily energy intake in terms of cheeseburgers, cyclists would have to eat 27 cheese burgers on some days to balance their expenditure.” Cheeseburgers would obviously be a mistake in sports nutrition terms, but you get the idea. Suffice to say, healthier lower fat alternatives would be much more bulky with fibre than cheeseburgers, so we’re talking about an immense amount of food here. Many researchers have concluded that a high carbohydrate diet is essential in maintaining energy levels during prolonged and repeated bouts of training and stage races like the Tour. Opinions differ slightly and range from 55% to 75% of dietary calories coming from carbohydrate.

Most modern opinions are much closer to 70% than 60% A few years back, I remember reading an article by Chris Carmichael (Lance Armstrong’s coach), published on a well known cycling website. His tour diet was broken down as being 67% carbohydrate, 13% protein and 20% fat. This is in line with much of the modern research, where 12-15% protein is recommended. Fat tends not to be recommended, but usually takes up the slack. 20% of calories from fat aren’t very much, especially when you consider how little of it you need by weight to take on a lot of calories.

Its all well and good figuring out how many calories a rider needs to take on board, but when does he consume them? There’s a limit to the amount of carbohydrate calories a rider can process while riding. As a general rule of thumb it works out at about a gram of carbohydrate per kg of bodyweight per hour. So a 60 kg rider would be able to consume and use 60g of carbohydrate per hour. Recent findings, again research mainly conducted by Dr Jeukendrup, have found that mixing Maltodextrin (a glucose polymer used in most reputable energy drink formulations) with Fructose (fruit sugar) significantly raises the amount of carbohydrate that can be absorbed and used. Results have shown up to a 40% higher carbohydrate delivery compared with Maltodextrin or glucose only formulations. The studies have also shown increases in power output whilst feeding on this 2:1 mixture. So it’s likely to be a nutritional strategy that the more switched on pro teams will adopt. For our 60 kg rider, the revised ingestion rates based on this formulation are looking to be approximately 1.4g of carbohydrate per kg of bodyweight each hour. This works out at 84g compared to the more traditional 60g. This is a staggering difference and one that’s brought about by the gut’s ability to absorb the glucose from Maltodextrin and fructose simultaneously without one impeding the absorption of the other. The riders will be consuming various energy products including drinks, gels and bars to optimise carbohydrate intake whilst keeping dietary fibre and fat to an absolute minimum. They will also be eating real food too, passed up to them from the team car.

Fat is the enemy when you’re on the bike for a couple of reasons. Firstly, it is just as easy for a rider to convert stored triglycerides (located under the skin and around the organs), to free fatty acids (the stuff that muscles burn) as it is for them to mobilise them from dietary triglycerides. So there’s really no point in consuming it. Secondly and more importantly, fat is satiating and dramatically slows down gastric emptying and the passage/absorption of food through the gut, so it’s a bit like a plug. A Tour rider won’t want to feel satiated when racing in these conditions, they’ll want to feel hungry again soon after a feed. That way they can get more useful calories in to their bodies as soon as possible. Carbohydrate is the limiting factor to sporting performance in an event like this, not fat, because carbohydrate storage in the body is strictly limited.

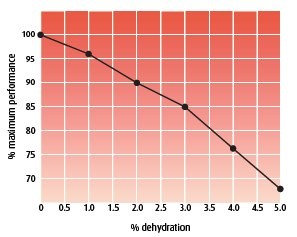

On Stage 17 of the Tour, it’s unlikely that any of the riders will reach energy balance over the 24 hour period between the stage starting and them beginning Stage 18. They’ll have a negative energy balance, which means that they will have burnt more calories than they are able to put back in. This is ok for a day or so, but these guys run at such a fine line between being the right weight to climb mountains efficiently and having enough energy and resources to get them through these taxing times. If any rider falls short of their calorie goal by an appreciable margin, they will blow their socks off, perhaps not on Stage 17, but quite possibly on Stages 18 or 19. What is ‘blowing ones socks off’? Basically it’s when the rider runs out of stored carbohydrate (It’s like someone switching the light off). Carbohydrate is the key to a rider’s metabolism, so if this runs out, everything shuts down. This is exactly what happened to Cadel Evans when he was leading the Giro in 2002. Hydration is of course of extreme importance. The diagram below is taken from a book called The Physiology of Sport and Exercise by Jack Wilmore and David Costill. It shows how an athlete will get a 5% drop in physical performance for every 1% of bodyweight lost through dehydration.

The trick for the riders is going to be about balancing fluid intake with carbohydrate intake. If the weather is particularly hot, which it’s likely to be, riders will hydrate more quickly with an isotonic or hypotonic drink mix.

This would be around 6% carbohydrates with electrolytes (salts), or perhaps a bit less. The problem with this is that although they’ll hydrate efficiently, they could fall short of their energy needs if they don’t drink enough. For instance, our 60 kg rider consuming a 2:1 Maltodextrin/Fructose based energy drink at 6%, would need to consume almost 1.5 litres of fluid per hour – even more if their drink was less concentrated than this. Strategies differ between individuals, but often a worthwhile one is for them to mix their drink at 6% and then pop an energy gel or bar in every now and then if they’re not drinking enough to satisfy their energy requirements. Tour riders will be popped onto a saline drip for re-hydration purposes at the end of the stage though, so dehydration rarely gets to a state of irretrievability. It’s interesting to note that on the stage of the 2006 Tour mentioned earlier on, Floyd Landis’ reportedly consumed no less than 70 X 480ml bottles of fluid over the five hour 23 minute stage. At 12 litres per hour, I wonder how much of this he actually poured over his head?

As soon as the stage finishes the riders will need to get a carbohydrate feed. There are plenty of recovery drinks on the market, but some teams or individuals will formulate their own. There’s a recovery window of about 30 minutes when enzyme and insulin activity is elevated, so the sooner they get a feed the better. Research recommends a 3:1 carbohydrate to protein mix (the protein further stimulates insulin production, encouraging a greater glycogen storage). Again, 1g of carbohydrate per kg of bodyweights recommended with the same ration of protein two, four and six hours post exercise, although the protein is only needed with the first feed. According to Melvin Williams, author of ‘The Ergogenics Edge’:

“For athletes who train intensely on a daily basis, including high-intensity resistance, anaerobic, or aerobic exercise, carbohydrate intake following exercise is needed to help return body carbohydrate stores to normal. Consuming a high carbohydrate diet, about 60 to 70 percent or more of daily calories as carbohydrate should help restore muscle and liver glycogen to normal levels and help you maintain high intensity workouts as needed on the following day.” Sound familiar? That’s because every author is saying the same thing. Riders will have a couple of big meals as a team, but they’ll be supplementing their calorie intake with all sorts of high carbohydrate snacks.

Jeukendrup outlines in his book how teams will use Maltodextrin as an invisible calorie to boost the carbohydrate content of food. The great thing about natural Maltodextrin is that it is almost flavourless, which means it can be added to food, especially things like sauces and soup without the rider even noticing it’s there. It contains no fibre and has the density of sugar, so it’s an absolute godsend in situations like this. Finally, before going to sleep, the riders will have a carbohydrate feed, usually in the form of an energy drink to take full advantage of the carbohydrate storage in the initial stages of sleep. Some riders will feed through the night too, either if they get up to go to the toilet or some will set an alarm.

So, other than the main macronutrients (carbohydrate, protein, fat and water), what supplements might the riders be taking to help them get through the stage – and the remainder of the race for that matter? The use of caffeine as a legal performance enhancer is well documented and will undoubtedly be used by the riders to help mobilise their fat stores, improve muscular efficiency and sharpen mental focus. There are the usual delivery methods such as tea, coffee and cola drinks, but these aren’t always convenient on the bike, so there is a variety of caffeinated energy gels available on the market, which represent a really useful delivery system. What else might the riders be taking to help them recover and power them through the mountains? Ed Burke’s book ‘Serious Cycling’ gives us a clue, because Dr Burke was consultant to Chris Carmichael, Lance Armstrong’s coach in the ‘good ol days’ so his recommendations must hold a fair amount of clout. Love him or hate him, Lance Armstrong has an undeniably successful history in the Tour de France and a string of performances that we’re unlikely to see repeated for a good many years. As well as mentioning caffeine, Burke refers (in this order) to Ribose, Glutamine, HMB, Glycerol, MCT and Carnitine. He also mentions Glucosamine for joint distress, but that’s more as a form of injury treatment than performance enhancer.

So what are these other supplements going to do for a Tour rider:

Ribose: There’s clear evidence that this supplement replenishes ATP stores within the muscle, which get wiped out during heavy exercise, so although this supplement won’t allow the rider to generate more power, it will significantly aid the recovery process, helping the rider to feel fresher (and generate his normal amount of power) on the following day. Three to five grams immediately post exercise is recommended.

Glutamine: This is the most abundant amino acid in the body, but your body will tear itself apart after exercise to make it available to fuel the brain and other vital organs, so supplemental glutamine immediately post exercise provides an alternative source, saving the rider’s muscles. Most good recovery drinks contain this nutrient anyway, but 6-10grams is required depending on your bodyweight. There’s not always enough in some products.

HMB: Much research has shown that this supplement has anabolic affects, boosting muscle size and strength. For endurance athletes it has a more ‘anti-catabolic’ effect, meaning that it stops muscle breakdown. It’s great insurance for riders concerned about whether they’re consuming enough protein (it’s a kind of bionic version of glutamine). Recommendations are for three to five grams per day.

Glycerol: Also known as glycerine turns you into a bit of a camel. If the riders know it’s going to be extremely hot and fluid losses are going to be huge, they may hyper-hydrate using glycerol supplementation. It’s a bit of a double-edged sword though, because hyper-hydration makes you heavier and that’s not a good thing for the steep Sage 17. The regimen is complicated, so not really for discussion here.

MCT: Is short for ‘Medium Chain Triglyceride’ and is a fat that is broken down quicker than standard dietary fat. This is the one exception to the fat rule, because this could actually be a useful fat? Research suggests that you add it to your carbohydrate drink, but this research was conducted way before the recent 2:1

Maltodextrin: Fructose research, so the temptation might be to ignore this one since this new information has come to light.

Carnitine: L-Carnitine is an amino acid-type substance that like caffeine helps to mobilise free fatty acids, making fat more accessible as a fuel. This has obvious carbohydrate-sparing and aerobic power connotations. Recommendations are between one and four grams per day at least two weeks before the benefits are needed. So there we have it, a little insight into the demands of this great race and what the riders might be doing to get themselves through it. The principles outlined in this article hold true for any of you undertaking a high training volume or back to back racing, so take all the information on board and use it. Just don’t even think about eating 27 cheeseburgers in one day—you won’t be thanking me. I should never have mentioned it. Actually, I’ll pass the buck. Dr Jeukendrup should never have mentioned it…