Over the past years, Germany has demonstrated an enviable pedigree when it comes to producing top-class sprinters on the WorldTour.

From 2012 to the 2017, almost one fifth of all Tour de France stages were claimed by German sprinters, a winning streak that also saw German victories on the Champs-Élysées for four consecutive years. In these years alone, John Degenkolb, André Greipel and Marcel Kittel collectively notched up 44 Grand Tour stage wins. What we’ve witnessed is a peak in Germany’s sprinter generation, with the schnelle Männer (fast men) undoubtedly shining not only on the roads of France, but indeed wherever else the WorldTour has taken them.

However, this run of success seems to have recently stalled somewhat. After dominating the sprints of the 2017 Tour, where he won five stages before crashing out of the race, a year down the track, Marcel Kittel is struggling to find his form.

He has admittedly been able to pull himself through rough patches in the past, and is quick to brush off his lacklustre season as nothing more than a side-effect of a slower than anticipated transition into the Katusha-Alpecin sprint train. However, the fact that he is yet to find his rhythm this deep into the season is far from encouraging.

The Gorilla’s Legacy Year?

Six years his senior, André Greipel is another German sprinting powerhouse who is finding himself facing a downwards slope in his career, a trajectory that could be potentiated by his move to the Pro Continental Team Fortuneo – Samsic next year. Despite his impressive 153 professional victories, the big results are increasingly eluding him, a fact that became particularly evident at this year’s Tour.

And then there’s John Degenkolb. After affirming his undeniable talent in 2015, the Thuringia native has been struggling to ride at the level he did prior to his horrific training accident in Spain. While it was encouraging to see him take a spectacular and well-earned win on Stage 9 of this year’s Tour, one can’t quite shake the feeling that he still seems to be weighed down by the physical and mental scars of his accident as well as subsequent injuries.

Enter: Pascal Ackermann

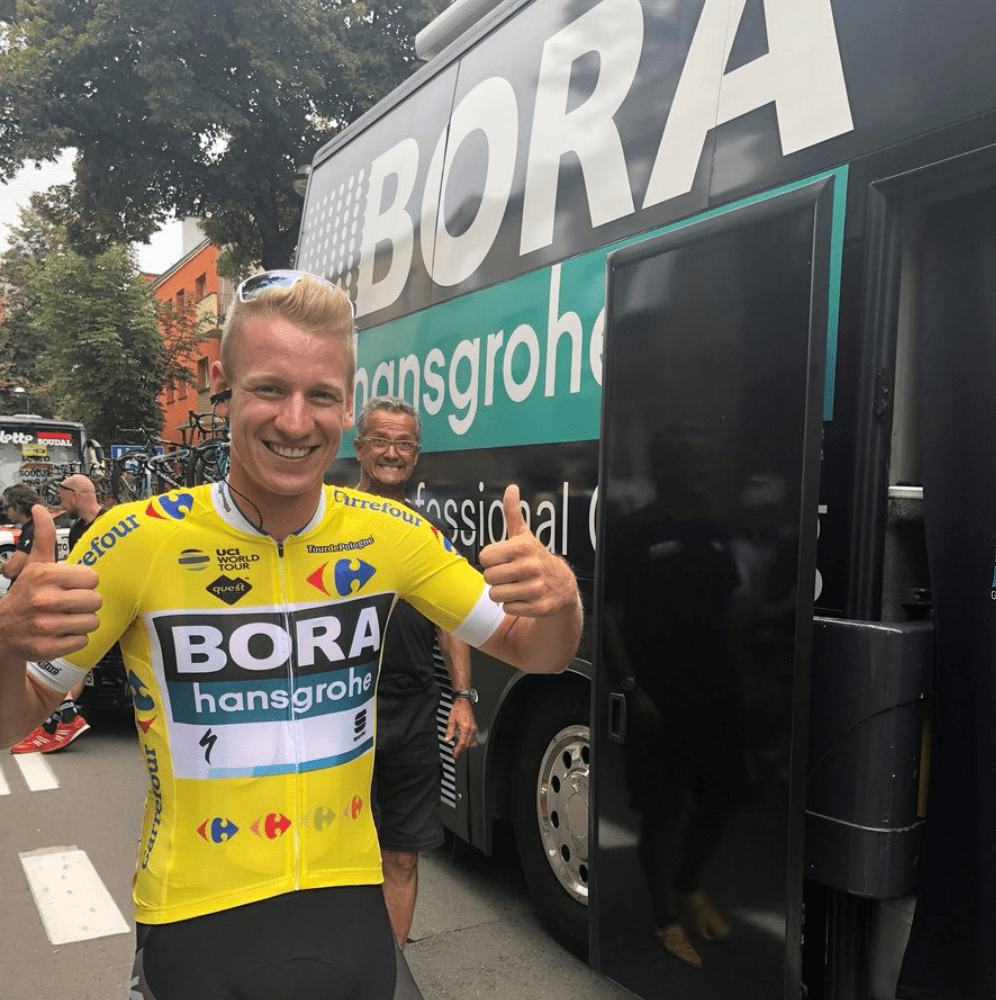

In the midst of these rather lacklustre performances by the familiar trio of German sprinters, 24-year-old Pascal Ackermann of BORA – hansgrohe has been busy making a name for himself. 2018 has been the season in which he joined the WorldTour winners circle after he claimed his maiden professional victory. In fact, all of his six wins this year have come at WorldTour-level races, an impressive feat for the rider from Kandel in southwest Germany, who would seem to have firmly inscribed his name on the prestigious honour roll of talented German sprinters with French first names. Yet despite being at the forefront of the bunch sprints this year, he is still sitting on the periphery of the cycling-following public’s wider consciousness.

Standing at over 1.80m and weighing almost 80kg, Pascal shares the impressive physical robustness of his compatriots, but at 24 years of age, he is five years younger than the youngest of the older guard, John Degenkolb.

A Change Of The Guard

If a picture tells a thousand words, then that picture might very well be that of the 2018 German road race championships podium, where Pascal firmly stood atop the first step, having defeated Degenkolb, who had to be content with second place. Greipel and Kittel were nowhere to be seen on the dias. A turn in the cog of the changing of the guard.

The newly-crowned national champion is an exciting future prospect not just for German cycling, but for professional cycling in general. His performances and increasingly solid palmarès should certainly be turning heads, if they have not already done so.

Pascal most recently exhibited his form this week at the Tour de Pologne, where he took out the opening two stages in impressive fashion. On stage one, without a dedicated lead-out of his own, he managed to outfox the well-oiled sprint train of the Belgian Wolfpack to launch a long-range sprint that stunned the field. He then backed this up the next day as he came from behind to power across the finish line in Krakow after a remarkable display of manoeuvrability.

These two wins came straight off the back of his victory at Ride London just one week prior, where, despite hitting the deck earlier in the race, he prevailed over the likes of Elia Viviani, André Greipel and Mark Cavendish, to name just a few. His title at the German national championships earlier that month put him on a four-race winning streak, which could very well have stretched out to five, had he not been boxed in on the third stage in Poland. A run of success like this is by no means a fluke.

The Road to Professional Cycling

For Pascal, it was almost an inevitability that he would somehow become involved in cycling. While his surname roughly translates to “farmer,” his family’s story is far from agrarian in nature. Instead, his entire family, from his grandparents to his siblings, share an unwavering passion for cycling.

He participated in his first race when he was 6 years old, and has held a racing license since he was about 7. But it almost wasn’t to be. He recalls how he cried inconsolably before his very first race because he didn’t want to take to the start. However, after some encouragement from his parents and receiving a trophy and the somewhat unconventional participation prize of a party horn, he became hooked on racing on two wheels.

While he was initially also fond of football, his interest in cycling naturally found greater support from his family, and at one point or another, the time came to make a decision between the two. Football offered no prize money in the most junior ranks, yet cycling presented an opportunity to line the pockets with extra Euros. With the prospect of bolstering his pocket money proving too enticing to resist, the mercenary young Pascal opted for cycling.

As a boy, he used to stand along the route of the Rheinland-Pfalz Rundfahrt, a five-day stage race which went past his house. He enthusiastically collected discarded bidons at the roadside, and as he became captivated by the escapades of the passing peloton, he was motivated to become a racer too.

His childhood heroes of course included the likes of Erik Zabel and Jan Ullrich. However, his biggest idol was Udo Bölts, a three-time German national champion who hailed from Pascal’s region of Rheinland Pfalz. As a youngster, whenever Udo was competing in a race, Pascal and his sister were sure to attend and collect an autograph from their cycling hero.

But Pascal is not like his idol, not least for the fact that Udo was a climber and Pascal a sprinter. While Bölts is often remembered for the unsavoury yet, we are assured, well-intentioned vociferation that he famously hurled at Jan Ullrich during the 1997 Tour de France, “quäl dich, du Sau!” (“push yourself, you ass,” to put it mildly), you would be hard pressed to hear such unwholesome execrations ever coming from Pascal.

Pascal Off and On the Bike

Although his explosive style on the bike has recently earned him the nickname “the German bomber,” his personality evokes the furthest thing from the images evoked by his moniker. With Pascal, there is no ego or bravado, and equally no sense of macho rodomontade that is usually so characteristic of sprinters.

He is an amiable character, loquacious in an unassuming way, and possesses a softly spoken and gentle manner off the bike. The genuine enthusiasm that he exhibits for racing during his post-race interviews is infectious. And this is not a veneer constructed for the media. He is the picture of an affable young man who is always quick to thank his teammates on the finish line, no matter the results. One would be hard pressed to find an individual that is more, for lack of better words, invariably cheerful.

It is difficult to imagine him getting caught up in the violent and ferocious clashes of the sprint finishes. But the tenacity is there. Much like his compatriot André Greipel, the young German champion combines a disarming friendliness off the bike with ferocity on it. His motto is “wer kämpft, kann verlieren. Wer nicht kämpft hat schon verloren” (“he who fights can lose, but he who does not fight has already lost”), a Brechtian aphorism that undeniably embodies his attitude towards racing.

At the same time, while he may be assuming a new mantle within the sport, he makes sure that he does not carry it too heavily. It’s important for him to still enjoy himself while competing, and in this respect his mindset is quite reminiscent of teammate Peter Sagan’s carefree “why so serious” attitude towards racing.

Stepping up to the WorldTour

It was no doubt this sense of measured dedication that caught the discerning eye of BORA-hansgrohe Team Manager Ralph Denk, who scouted Pascal while he was riding for the Continental team Rad-Net Rose, where he raced from 2013 to 2016.

Signing on the dotted line with the German WorldTour team as a neo-pro ahead of the 2017 season opened up a new chapter in his career. Following an introductory year with the team that was spent learning how to navigate the WorldTour ropes, in his second year in the pro peloton, seemingly undaunted by its sheer depth of talent, Pascal has almost seamlessly slotted himself into the fold.

In discussions with team management last year, it was decided that he would be given an opportunity to prove himself as a sprinter in 2018. Despite the fact that his team is replete with on-form fast men such as Peter Sagan and Sam Bennett, he has managed to find opportunities to gain experience as a sprint leader this year.

His early season produced some solid and promising results. He placed third on two occasions at the Abu Dhabi Tour. He was also a serial podium finisher at the semi-classics, coming third at Handzame, second at Driedaagse De Panne, and second at Scheldeprijs, the unofficial sprinters World Cup.

In all three Belgian races, as has become the common narrative of this Spring, the young German had to watch a Quick-Step rider raise his arms in victory ahead of him. After having specifically earmarked these events as a season target, he was disappointed to leave the country without a win.

It was beginning to look like he might be the next rider to be begrudgingly crowned with the unenviable title of “eternal runner up.” However, he accepted his results with the level-headed equanimity for which he is known, admitting “I’m disappointed because I really wanted to win, but I’m still happy to be on the podium.”

At Handzame he went too early in the sprint, and five days later at De Panne he went too early again. A pattern was emerging, yet it was one from which he would swiftly learn.“Better too early than never,” he joked with me from the finish line after missing out once again to a Quick-Step rider, his unwaveringly sanguine nature showing through in a situation that would have turned any other bright eyed youngster into a bitter defeatist.

The Wins Begin

To anyone that watched Pascal compete in these early season races, it appeared certain that he was on the cusp of that long sought after maiden professional victory. In Belgium, he had demonstrated that he is able to nail his positioning and has a sharp instinct for the fast finishes.

These first few podium placings were indeed auspicious results, and it wasn’t long before he went on to take the victory that had eluded him throughout the Spring, when he won Stage 5 of the Tour de Romandie. His elation following his first hard-fought professional victory was palpable, and it proved to be a turning point of sorts. Not long afterwards came his sprint victory into Belleville en Beaujolais at the Dauphiné, and from there he hasn’t seemed to have broken stride. The results have kept on coming, with his momentum taking him to subsequently win the German championships, RideLondon and the two opening stages of the Tour de Pologne, all in succession. He is no longer a “nearly man.”

The Future

Next, he is slated for the EuroEyes Cyclassics Hamburg, the Deutschland Tour, GP de Fourmies and Sparkassen Münsterland Giro, before concluding his season in China. While a participation and stage win at the Tour de France is a goal that he is admittedly now eying, he concedes that this next step probably won’t come in the most immediate of futures. He does, however, hope to ride a three-week Grand Tour beforehand, when the time is right. Given his current trajectory, a participation, if not indeed success, at a major three-week race would seem an inevitability, and his ascendency to the lofty heights of cycling’s highest echelons of sprinters would be more than well-deserved.

In the meantime, the young German should certainly be earmarked as a talent to watch. After all, the people who know him best, his hometown of Minfeld, have such belief in him that they decided to name a street in his honour, and have cemented a post across from his parents’ house which reads “Pascal Ackerman-Weg.” This, if nothing else, is surely a sign of things to come.