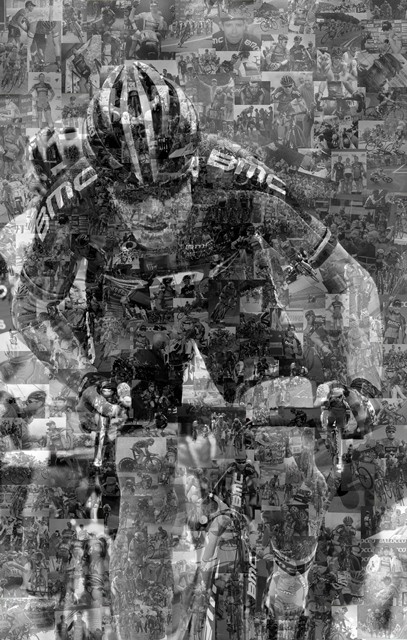

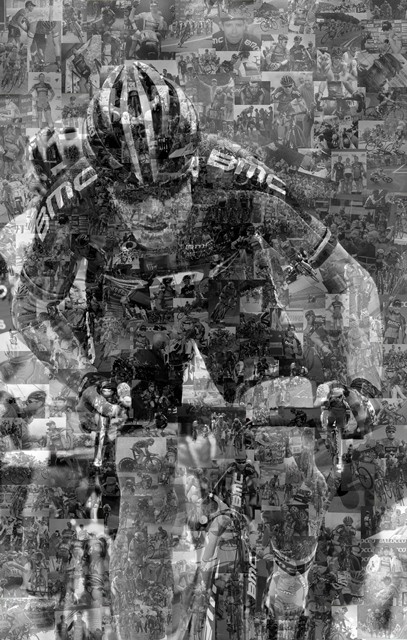

After 14 roller-coaster years as a professional road cyclist he left his final road world championships without a trace. But more comfortable in obscurity than out of it, Cadel Evans, now that he’s got the chance to reflect, should be in awe of himself for everything he accomplished and everything he stands for.

After 14 roller-coaster years as a professional road cyclist he left his final road world championships without a trace. But more comfortable in obscurity than out of it, Cadel Evans, now that he’s got the chance to reflect, should be in awe of himself for everything he accomplished and everything he stands for.

I can’t believe I did it for so long or that i was so good at it. It’s hard to stay that motivated. It’s like a flame goes out inside you, which has been flickering for the last year or so. And when it goes out completely you look back and you’re kind of in awe of your younger self. I find it unfathomable now.”

These could easily be the words of Cadel Evans but they’re not.

Instead, they’re from one of his contemporaries who retired a few months before he did, on September 28 last year, the day of the elite men’s road world championship.

Like Evans, Scotsman David Millar was hugely talented right from the get-go, using his prowess against the clock to win the opening stage of the 2000 Tour de France on debut and the 2003 time trial world championship, catapulting him into the limelight, before he found his nadir less than a year later when he was arrested at his home in Biarritz and confessed to having used EPO.

Stripped of his world title and banned for two years, the post-suspension Millar became a vocal anti-doping advocate, and while not quite as successful as the rider he was before, he was still better than most of his contemporaries. National road and time trial champion, Commonwealth Games champion (time trial), stage wins at the Giro d’Italia, Tour de France and Vuelta a España, and a silver medal in the time trial at the 2010 worlds.

His last win came on Stage 12 of the 2012 Tour de France, emerging triumphant after a day-long escape on the longest stage of that year’s race, so when he decided to hang his wheels up in Ponferrada, Spain two years later and after 17 years as a professional, he knew his time was nigh.

“It just feels right,” he told the London Telegraph on the eve of captaining the British team in the 254.8km elite men’s race in Ponferrada last September. “These are people I have been through thick and thin with over many years, since I was a junior. Even the hotel feels right. It wouldn’t be right if it was a luxury hotel. This is a nice reminder of what it (professional cycling) is actually like.”

Nursing a hand injury from a crash on Stage 15 of the Vuelta three weeks previous that left him with a cracked rib and fingers bandaged – he still finished the race, 144th out of 159 finishers, and four-and-a-half hours behind overall winner, Alberto Contador – he told reporter Tom Cary in Spain he could not grip his handlebars the way he needs to, but such is life. “I mean, I can’t get on the drops so I wouldn’t be much use in a sprint. But I won’t be in one anyway. It’s not cool and it’s a real shame as I felt so good at the Vuelta. The fitness is great. It’s not how I wanted it to end but – again – that’s life. That’s pro racing. This is the shit we put ourselves through.”

Yes, it’s easy to forget what these guys do for their job. When some of us look for a reason to ‘chuck a sickie’, professional cyclists scour for any reason not to quit.

At the Vuelta, Evans, like Millar, had plenty of reasons to abandon his last Grand Tour – form, fitness, motivation – but if he was to stand any chance of making a go of it at the road world championships, a race he emphatically won five years before and became the first Australian to do so, he needed to finish it. His best results came on the third and tenth stages where he placed sixth in both, but he was a long way off his form four months previous at the Giro where he ran eighth overall, and a metaphorical mile off his 2011 Tour-winning best; as an athlete, a state of mind and body he would not discover again.

Nonetheless, and true to form, he soldiered on finished the Vuelta. In 52nd position overall and compared to Millar, a mere two-and-a-quarter hours behind ‘El Pistolero’ Contador, who returned from a busted knee at the Tour and found salvation in Spain, his home tour. Notably, however, Evans said sometime in the final week his “mind was elsewhere” – a mindset once anathema to him when a race number was pinned to his back.

Still, we hoped – Australia hoped – for a return to the

Cadel of Old in Ponferrada.

His 2009 season, by comparison, was not brilliant: two stage wins, 28th at the Tour and third at the Vuelta. Yet he somehow pulled a rabbit out of the hat in Mendrisio, a stone’s throw from his Swiss home where he lives with his wife Chiara and adopted son Robel, to become Australia’s first – and still only – road world champion.

Heading into the Sunday of the race he was not touted as a leader per se – that went to Simon Gerrans and Michael ‘Bling’ Matthews – though it was not a dissimilar situation to Mendrisio, where he was a protected rider but not the outright leader of the national team. There in Switzerland, by virtue of his actions, he made

himself the outright leader, first of the team, then of the peloton, where, one by one, he rode all and sundry off his wheel to reveal a side of him we had not seen before; an impetuous, more attacking Cadel that, two years later, would re-emerge to set another Australian first, that of course being champion of the Tour de France.

His now departed coach Aldo Sassi told him that if he won both the Worlds and the Tour he would become “the most complete rider of his generation” and so, on 24 July 2011, on the world-famous boulevard of the Avenue des Champs-Élysées, it came true. Sadly, Sassi was no longer with us to see it, but from that point onwards, I felt anything Evans achieved could be considered a bonus.

Naturally, he attempted to repeat the feat the next year but finished a disappointing seventh in the 2012 Tour, beset by a virus that disallowed him from rediscovering his best. He called it a season as early as August, after posting a DNF at the USA Pro Cycling Challenge in Colorado, yet ironically, began the 2013 season no earlier; in fact a little later than usual at the Tour of Oman, where he finished third overall behind Christopher Froome and Contador.

The Strade Bianche, Tirreno-Adriatico, Critérium International and Giro del Trentino followed, before deciding upon a late undertaking at the Giro d’Italia, or rather having it decided for him, since it was not on his original race program. There in Italy’s Grand Tour, Evans proved himself to still be competitive, finishing third overall behind Vincenzo Nibali and Rigoberto Uran – albeit almost six minutes in arrears of the Sicilian they nickname ‘lo Squalo di Messina’, or the Shark of Messina, who 10 months later would put on an equally imperious display

to claim victory at the Tour while Froome and Contador fell and faltered.

Following a second consecutive lacklustre Tour for BMC Allan Peiper came on board as sporting manager, essentially displacing John Lelangue. A conversation behind closed doors in October 2013 saw Evans given a talking to by his compatriot and elder statesman, and he was caught by surprise: no Tour in 2014 – the future was now American Tejay van Garderen, and a team would be built around him and him only – but a team would also be built around Evans, with the mission to win the Giro.

“Cadel can win the Giro. That is a fact. You cannot do both (the Giro and Tour), not at his age, not in this era,” Peiper told VeloNews correspondent Andy Hood at last year’s Tour Down Under. “Realistically, he can win the Giro. Going up against guys who are there, it’s not realistic he can win the Tour again… It’s time to pass the baton.

“It was a little bit of a shock for Cadel (to hear he would not ride the Tour). He never really sat down and thought about making the Giro his mission. For him, the Tour has been the biggest part of his life more than a decade. Letting that go wasn’t easy.”

Second to Simon Gerrans at the national road championships in Buninyong, second again to Gerrans at Down Under by two seconds, it appeared, at least initially, Evans had indeed let go and come to terms with his newfound role and objective. But when he returned to Europe, things, for one reason or another, began to head south.

However as the May 9 Grande Partenza in Belfast loomed, the plucky Evans, unwilling to accede to his aging body, managed to straighten himself out. From a DNF at Tirreno-Adriatico in March to seventh overall at the Tour of the Basque Country in early April, then a fortnight later, two stage wins and overall victory at the Giro del Trentino.

He was on track for the Giro; on track to win the Giro, maybe.

Avoiding mishap in a sketchy opening week and well protected, Evans assumed the race lead, or maglia rosa, after eight stages from Bling Matthews. He enjoyed a 57-second buffer to Uran and should have at least held, if not opened, his advantage on the 42.2km Stage 12 individual time trial in Barbaresco; although he did not tank it he nevertheless conceded 1’34 and the race lead to the Colombian. He maintained his second place overall until the topsy turvy stage to Val Martello, where another Colombian, Nairo Quintana, took the race lead in controversial circumstances amid a snowstorm. From third to ninth then back to seventh then, finally, eighth…he would finish a whopping 11 minutes, 51 seconds behind Quintana, a man 13 years his junior. Evans’ days as a Grand Tour rider, let alone a Grand Tour winner, were effectively over.

For the first time in a decade he would ride the Vuelta, what would be his last three-week race, in a support role for his equally aging team-mate Samuel Sanchez, just a year younger than he. His back well and truly to the wall, it was also a last-ditch effort to give himself an outside chance in what would be his final world championships, the men’s race slated to run a fortnight after the end of the Vuelta.

Like Millar, he left Ponferrada as he left Florence the previous year, with a DNF, and without a trace. Not ideal, surely not how either of them wanted it to end, but such is pro bike racing. Such is the life of a professional cyclist. “the shit we put ourselves through.”

Like Millar the flame had been flickering for some time before his February 1 retirement this year at the eponymous Cadel Evans Great Ocean Road Race.

But like Millar, when the flame goes out completely and he takes time to look back on 14 roller-coaster years as a professional road cyclist which encompassed euphoric highs interspersed with hellish lows, some out of his control, Evans should be in awe of himself for everything he accomplished, everything he stands for and a life as far from half-lived as you can get.